BY ANNA MARÍA BOGADÓTTIR

Over the course of a few years, the number of annual visitors in Iceland grew from half a million to two million. While the rapid growth surely benefited the economy, it came hand in hand with signs of over-tourism, causing red alerts and closures of popular nature sites due to excessive intrusion. While creative landowners responded to the situation by becoming tourist operators, the government launched a series of official plans, funding schemes and other initiatives. The aim was to coordinate research and prepare to develop physical and human infrastructure that would ease access to and protect the primary attraction: Nature.

Icelandic nature and tourism

In flux between glaciers and volcanoes

Iceland is a volcanic island located in the North Atlantic Ocean, 300 km east of Greenland and 900 km west of Norway. The Arctic Circle runs through the island of Grímsey, 40 km north of mainland Iceland. Due to Iceland’s location, north of the Central Atlantic, its nature and ecosystems are particularly fragile.

Interactive Map

The surface area is 103,000 km², but most of the 376 thousand inhabitants live close to the coastline, spanning over 500 km. The population density is four people per km². Iceland’s landscapes are shaped by the forces of nature, varying from snow-capped mountains and staggering waterfalls, deep fjords and valleys formed during the ice age to vast volcanic deserts, black sand beaches, gushing geysers, natural hot springs, and lava fields as far as the eye can see. About 10% of the land area is covered by receding glaciers. Scientists predict that they may largely vanish in the next 100-200 years, which will drastically change the landscape.[1]

Iceland’s climate is subpolar oceanic, with cold winters and cool summers, although the winters are milder than in most places of similar latitude due to the Gulf Stream, which ensures a more temperate climate in Iceland’s coastal areas all year round. The Gulf Stream also results in abrupt and frequent weather shifts, which is why one may experience four seasons in one day. Iceland does not have a rainy season, but precipitation peaks from October to February, with the southern and western parts receiving the most rainfall. In the North, East and inland, there are colder winter temperatures but warmer summers and noticeably less snow and rain. Iceland’s most influential weather element is the varying types and degrees of wind.

The appeal and image of nature

For centuries, Iceland has been a destination for international scientists and artists aiming to study and experience volcanoes and glaciers as well as the Icelandic society and its culture. Fictive and real landscapes have served as the setting for narratives from Norse mythologies written in the 13th century, 18th-century travel journals, 19th and 20th-century adventure novels, and recent films such as Star Wars, James Bond, and Game of Thrones. Taken together, these narratives create a general idea of destination nature experiences, as is currently visually exhibited on Instagram and other digital platforms where the idea of the destination Iceland continues to be moulded by influencers.

Since the mid-twentieth century, Iceland has worked towards increasing the number of foreign visitors. It grew slowly during the 20th century up until the 1990s. A significant part of those who travelled to Iceland used to be experienced nature-lovers, geared with analogue maps and compasses, ready for camping and hiking in remote areas without any designated infrastructure. The visits grew steadily in the second half of the 20th century, with a total of four million foreign tourist arrivals from 1950 to 2000. After the economic meltdown in 2008, the Icelandic government increased its focus on tourism as a potential rescue line for foreign currency, with the Icelandic krona in free fall. Furthermore, the Eyjafjallajökull eruption in 2010 put Iceland on the map by bringing flight travel to a halt in large parts of the world. Fearing a negative impact on the country’s growing tourism industry, Iceland launched the most extensive tourism campaign to that date, called “Inspired by Iceland”[2]. However, the campaign proved somewhat unnecessary, as the eruption significantly increased interest in Iceland as a destination. In addition, the drop in the local currency made Iceland a less expensive destination and thereby in reach for a larger group of visitors than before. Hence, the tourist surge following the Eyjafjallajökull eruption came hand in hand with export-led economic recovery plans emerging from the 2008 financial crisis. This resulted in exponential growth in the number of foreign visitors. Whereas tourism doubled between 1997 and 2007, the number of tourists grew 500% between 2010 and 2017, peaking at 2.5 million in 2018[3]. The sudden increase was followed by a slight decrease in 2019 and a sudden stop in 2020, caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. A short sequence that could resemble a rollercoaster ride.

In spring 2021, the area of Geldingadalir metamorphosed into an accessible erupting volcano midway between Keflavik International Airport and the capital city of Reykjavik. Overnight, the priorly unknown area became a pilgrimage site for scientists and local and foreign visitors alike. Regularly on the news, geologists referred to measurements and monitoring to predict the future of the volcanic activities, all the while stressing that nature behaves in unpredictable and uncontrollable ways. In contrast, engineers presented their experiments and calculations for plans to control the lava flow. On one hand, nature was viewed as a force beyond human control, and on the other, a controllable phenomenon, a force to be tamed.

The right to nature and nature’s right

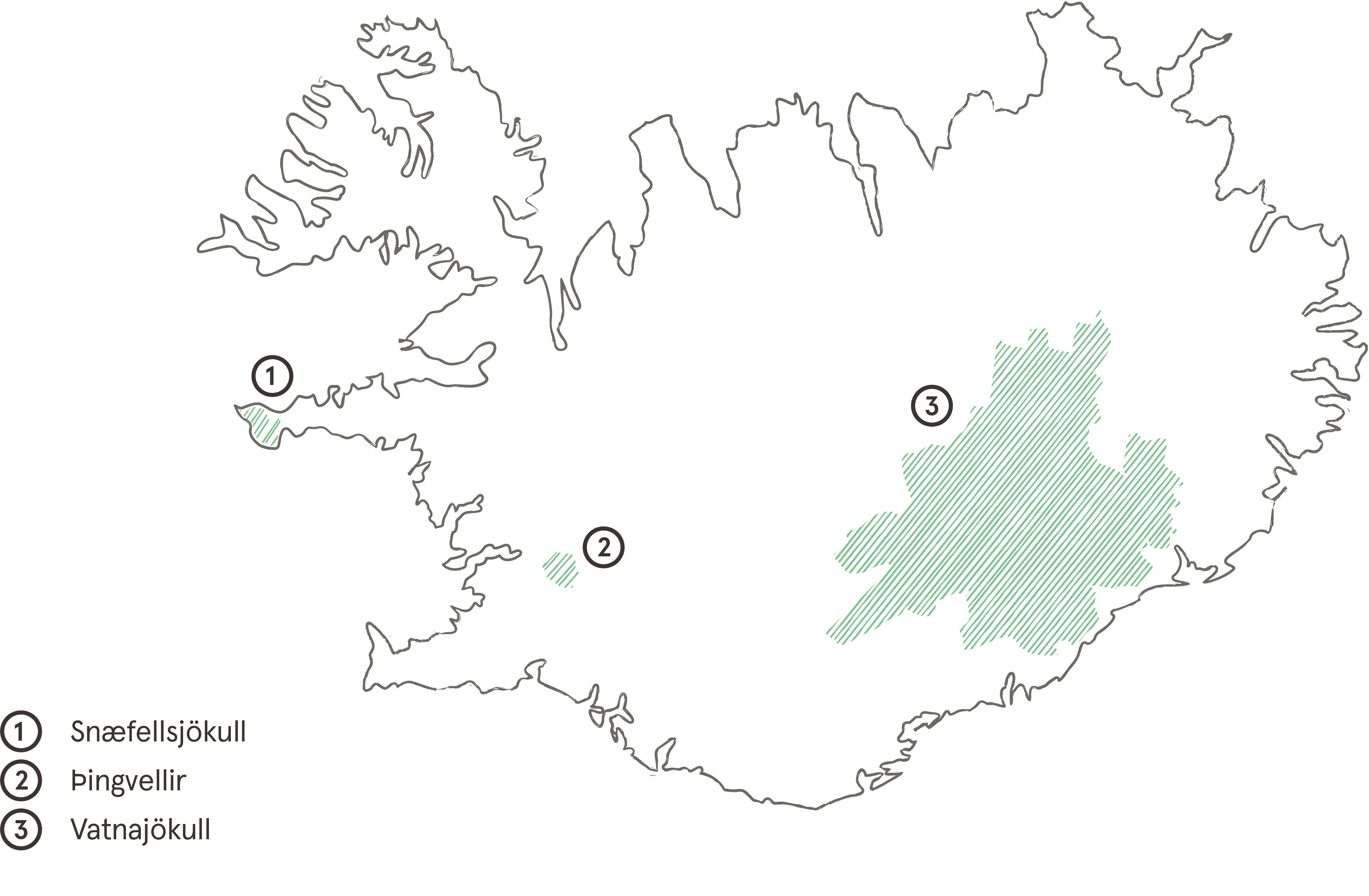

“The public is allowed to travel on the terrain and stay there for legitimate purposes. This right is accompanied by an obligation to take good care of the country’s nature,” states the nature conservation law stressing that people should show full consideration for the landowner and other right holders [...] and follow their guidelines and instructions regarding travel and handling around the country[4]. The nature conservation law also defines the different types of protected areas, including national parks, with the common purpose to preserve the nature of the area, allow the public to get to know and enjoy its nature and history, promote research and education about the area and strengthen economic activities in the vicinity of the national parks. There are 115 protected areas in Iceland, hereof three national parks, of which two are designated UNESCO Heritage Sites.

Þingvellir National Park, a designated UNESCO World Heritage site since 2004, was initially established in 1928 when it became the first protected site in Iceland. Located in the southwestern part of Iceland, about 50 km from the capital, Reykjavík, Þingvellir National Park covers an area of 228 km²[5]. The history of Þingvellir, from the establishment of the Althing around 930, gives an insight into the spatial setting of the democratic forum of the Icelandic republic during the Viking Age, which, together with various natural phenomena, create a unique cultural landscape. From the settlement of Iceland, Þingvellir has been a destination for travellers and the site of national festivals. Originally, Icelanders travelled to Þingvellir to attend large feasts in relation to the annual parliamentary session. Now, it is amongst the most visited sites in Iceland, with service buildings, information centres, and an increasing number of constructed pathways and viewing platforms to enable access to different nature sites while protecting vegetation from the pressure of growing numbers of visitors.

Vatnajökull National Park is the second-largest national park in Europe, covering close to 14% of the total surface area of Iceland, including the Vatnajökull glacier, the largest glacier in Europe. It was established in 2007, merging a few previously protected sites into one. In 2019, Vatnajökull National Park was approved by the UNESCO World Heritage List, based on its unique nature and diverse landscapes created by the interplay of volcanic activity, geothermal energy, and streams with the glacier itself[6].

Snæfellsjökull National Park is located on the outskirts of Snæfellsnes in western Iceland. It is about 170 km² in size and the country’s first national park to reach the ocean.

In addition to the national parks, Reykjanes Geopark at the Reykjanes Peninsula and Katla Geopark in South Iceland have been included on the new UNESCO list of geoparks recognising “the importance of managing outstanding geological sites and landscapes in a holistic manner”[7], in accord with the definition that “a UNESCO Global Geopark uses its geological heritage, in connection with all other aspects of the area’s natural and cultural heritage, to enhance awareness and understanding of key issues facing society, such as using our earth’s resources sustainably, mitigating the effects of climate change and reducing natural disaster-related risks.”[8]

Fragile and life-threatening nature

Due to the sudden and immense growth in visitor numbers in the early 21st century, many natural sites in Iceland became significantly affected. Where the road system and the urban milieu escaped, the Icelandic host faced challenges greeting its guest, no longer a trained hiker, but nevertheless wandering in untouched landscapes, not aware of its danger nor fragility and unfamiliar with the codes of conduct known to the experienced hiker.

Along with nature protection rapid development of infrastructure had to be undertaken in order to accommodate travellers’ primordial needs when off the grid and to promote the security of visitors sometimes threatened by weather and site conditions. Small- and large-scale infrastructures were to be designed and constructed. Ranging from hiking paths, viewing platforms and natural spas to the construction of new hotels in the capital area and the expansion of the Keflavík International Airport. All the while, the previous local store in the village became a souvenir shop, and large shipments of rental cars came ashore to bring travellers out of the city and into nature.

Economic pressure and investment in small-scale infrastructure

In 2015, the tourist industry had become the most important export sector for Iceland, and in 2016, the share of tourism in GDP exceeded the share of fisheries which had previously been on top. The proportional importance of the tourism industry had become far greater than in most OECD countries [9]. Simultaneously, the travel period, previously mainly in the summer months, had been extended with increased winter tourism presenting other types of dangers and infrastructural needs than summer travel.

Facing rapid growth in tourism, Iceland increased its investments in small scale infrastructure. In 2011, The Tourist Site Protection Fund, hosted and serviced by The Icelandic Tourist Board, began its operations. The fund's purpose is “to promote the development, maintenance and protection of tourist sites and tourist routes throughout the country, thereby supporting the development of tourism as an important and sustainable pillar of the Icelandic economy. It also aims to promote a more even distribution of tourists throughout the country and to support regional development”[10].

More than 700 projects received funding from The Tourist Site Protection Fund between 2012 and 2020, amounting to around five and a half billion ISK. Contributions to the fund have increased significantly. In 2012, the fund had 69 million ISK at its disposal, but in 2020, the amount had grown to 700 million ISK. Initially the funded projects were mostly initiated by the state or municipalities but in recent years, projects by smaller parties, individual landowners and associations have increased considerably. Cooperation between private and public stakeholders on a regional level has gained more attention. In 2015, the Icelandic Tourist Board and the Tourism Task Force launched the development of Destination Management Plans (DMPs). Working towards coordination of development and aiming for management of flows in each region while strengthening regional initiatives.

As of now, The Tourist Site Protection Fund operates in three main focus areas. Firstly, nature protection and safety, focusing on projects related to nature conservation and visitor security. This can involve directional paths and platforms that guide visitors with the aim to regenerate and protect nature on the site. Secondly, the development of tourist attractions, favouring projects related to the development, construction and maintenance of built structures. And third, design and planning, such as changes to municipal plans, and design of foreseen development and construction. Projects can receive funding for design and planning and later another grant for construction. Initially, grants from the fund were mainly targeted to popular sites but there is increased emphasis on spreading the load by creating new magnets in less visited regions and to support regional development on the basis of destination plans. However, according to an evaluation report on the The Tourist Site Protection Fund, despite greatly increased budgets, there is still an urgent need for more investment [11].

National plan for the development of infrastructure for the protection of nature and cultural heritage

Since 2018, The Tourist Site Protection Fund has been reserved for projects owned or managed by municipalities and private parties. Projects on sites operated by the state, like national parks and preserved areas, receive funding from a national programme to develop infrastructure for the protection of nature and cultural heritage, a strategic twelve-year plan with a policy for infrastructure development on tourist sites and routes. The programme sets goals for site management and sustainable development, protection of nature and cultural heritage, security, planning and design, and tourist routes. A three-year project plan sets out proposals for concrete projects in parallel with the strategic plan.

The board behind the national programme includes representatives from four ministries and the Association of Icelandic Municipalities. In addition, from 2019 through 2021, there was an active Coordination Group with representatives from public institutions; three national parks, Icelandic Forest Service, The Soil Conservation Service of Iceland, The Cultural Heritage Agency of Iceland, The Iceland Tourist Board, Icelandic Association of Local Authorities and Iceland Design and Architecture (ID&A). The group was assigned to define projects to promote professional knowledge, increase quality in design and coordinate the development of infrastructure to protect natural and cultural-historical monuments in tourist sites. ID&A, whose role is to facilitate and promote design as a vital aspect of the future of Icelandic society, economy and culture, was commissioned to pursue and implement some of the projects on behalf of the Coordination Group. These projects were gathered with other relevant projects, including the Nordic project Design in Nature, under the umbrella of Góðar leiðir, Good Paths. A platform for coordination and collaboration between different operators to facilitate access to toolboxes, guidelines, and instructions to project owners and operators. Among them an update of a coherent signage system, originally from 2011 Vegrún, a manual for construction of nature paths nature paths, and guidelines for planning procedures for tourist sites.

Additionally, the Coordination Group has commissioned educational programmes for nature regeneration and best practices in designing, planning, and constructing infrastructure in nature sites. The group’s formal mandate ran out in 2021 and it remains to define further measures of the initiative.

Beyond the tolerance level

“Nature is the main attraction of the Icelandic tourism industry, and systematic efforts are being made to protect it with stress management and sustainability as a guiding principle,” reads Vegvísir í ferðaþjónustu from 2015[12]. Looking back, it can nevertheless be said that the design and implementation of small-scale infrastructure as protection measures for nature came more as a reaction rather than a carefully thought-out plan. In 2015, somewhat in a state of emergency, Stjórnstöð ferðamála, the Iceland Tourism Management Board, was established as a temporary initiative aiming to get an overview of the situation and coordinate research to prepare for action. Focusing on coordination between different sectors, the management board coordinated research on tolerance limits, concentrating primarily on the number of tourists. The Iceland Tourism Management Board’s focus areas were defined as positive tourist experiences, reliable data, nature conservation, competence and quality, increased profitability, and branding Iceland as a tourist destination.

Measuring tools

Data collection on different sites has been facilitated with instruments that measure the number of visitors. Other official measuring initiatives include The Tourism Balance Sheet, an extensive measuring tool for regularly assessing the impact of tourism on the environment, infrastructure, society, and the economy. Initiated by the Minister of Tourism, Industry and Innovation, the project was managed by the Icelandic Tourist Board and developed by EFLA Engineering together with consultants from Tourism Recreation & Conservation (TRC) from New Zealand and Recreation and Tourism Science (RTS) from the United States. The aim is to create the basis for policymaking and prioritising measures to increase coordination. Sustainability indicators were developed based on the tolerance limits of the environment, society, and the economy[13]. On a range of protected areas under official authority the assessment tool has been applied, facilitating the prioritisation of intervention and investment at a given site. However, the defined parameters for measurement assess only the condition of structures and nature at a particular site. More qualitative and aesthetic assessment tools would be a valuable addition to the balance sheet at hand.

Official quality control system

One of the latest government initiatives in sustainable tourism promotion is Vörður, a holistic approach to destination management based on the French model, Réseau de grand sites de France, which defines the framework for destinations in Iceland that are considered unique nationally or globally. The project is managed by the Ministry of Tourism. The first destinations to start the process are Gullfoss, Geysir, Þingvellir National Park and Jökulsárlón. The ambition of establishing such a quality assessment system was initially set in Vegvísir fyrir ferðaþjónustu (Guidelines for tourism) in 2015 [12].The plan is that by 2022, more sites, including privately owned tourist sites, can apply for assigned membership in the quality control system. Sites assigned with the label Vörður are seen as models for other destinations, fulfilling quality criteria in terms of management, supervision, organisation, facilities, services, nature conservation, safety and more. The sites must demonstrate a long-term commitment to implementing defined management and planning standards, including design, accessibility, education, security, load management and digital infrastructure.

Design traditions and local craftmanship

Infrastructure of an agricultural society becomes a framework of leisure for the urbanite

Design tradition and local craftsmanship

Small-scale infrastructure in Icelandic nature reflects the geology of Iceland and ingenious use of local building materials, and a story of a nation shifting rapidly from an agricultural to an urban society in the wake of the 20th century. Abruptly, Icelanders were distanced from living with, in and off the land, growing a seed of longing of that exact nature for repose and experience.

Following the introduction of the first motorised fishing vessel at the beginning of the 20th century and the construction of a sturdy stone pier in Reykjavík, fishing replaced agriculture as the primary industry, keeping its status until the 21st century when the tourist industry took over. Revenues from the fishing industry set the stage for urbanisation throughout the 20th century, together with the birth of the Icelandic urbanite who no longer lived with nature but longed for it. Accordingly, a new perception of nature appears in the artworks and literature of the early 20th century, portraying nature as something beautiful and even sublime, yet distant. The prints of artworks by the “Icelandic masters”, framing the solemnity of nature, ended up on a wall in the living room of a new apartment of sons and daughters of nature who now lived in the city.

Until the 20th century, turf farms were the characteristic habitat of Iceland, nestled in the landscape, leaning from the wind with thick earth walls creating good insulation. The grass roofs grew naturally from the landscape, creating small hills as seen from the exterior perspective. In the early 20th century, concrete became Iceland's local building material. Hence, the texture of the built environment jumped directly from earth to concrete, made of volcanic sand abundant in the estuaries and beaches along the coast.

In parallel with urbanisation in the 20th century, outdoor leisure activities grew steadily with a surge in hiking, mountain skiing, recreational fishing, and bathing. In the 1920s, the first outdoor hut to support leisure activities in nature was built in Lækjarbotnar, close to Þingvellir. Iceland Touring Association (FÍ) was founded in 1927. Today, the association runs 40 mountain huts across Iceland, mainly along the most popular hiking trails.

As part of a swimming education movement in the first decades of the 20th century, local communities in many areas constructed local and outdoor swimming pools, often close to hot water sources that previous generations had bathed in. Weathered and sensitive structures from history, these pools have later attracted travellers and later, at times, excessive intrusion and damage like in the examples of Seljavallalaug and Hrunalaug.

Cairns, conical structures of stacked stones laid decades and even centuries ago, still serve as signposts in Icelandic landscapes where people have wandered since the island’s settlement. Together, the cairns in the open landscape create negative lines indicating old routes for hikers and horse-riders, travelling with goods and running errands in all weather in the agricultural society, usually taking the shortest route over hills and mountains between the distant farms. Apart from guiding the way, the cairns would serve as information infrastructure, as wanderers would sometimes leave notes between the rocks, a poem, a gentle word on how to proceed, what to be aware of, or what to look for. The type of stones used for these conical structures varies from area to area, from old basalt rock in the east and west to younger lava stones in areas on top of the Mid-Atlantic-Ridge, which lies underneath Iceland from the southwest through the northeast – demarking the zones of volcanic activity. This variety of building materials and building techniques is also found in other historic structures like trails, pathways, steps, walls, and fences laid by different stones, with local versions in each part of the country. The differences are explained by specific knowledge passed on through local craftsmanship and the natural material palette depending on the geological formation of each area. Along the old routes, there were huts built to shelter wanderers and farmers herding sheep from the highlands before the first snow. Like all other habitats, these huts were initially built of local material, mixing stone, rock, and earth with wood, which was scarce and therefore used sparsely and thoughtfully. A built lesson in sustainable design and building methods that warrants further study to unleash its potential in relation to future design in nature.

Current designs and future visions

Pristine nature, now with full service

The twenty-first century has given Icelandic natural landscapes a new purpose as part of a recreational itinerary and experience of the global citizen welcoming the open invitation to seek temporary physical and mental recovery from the hazy urban world. Therefore, tourism has instigated new forms of urbanisation in remote areas and natural landscapes that can be observed through urban interdependencies within Iceland and beyond. As a result, the typical traveller in Iceland is no longer the experienced nature hiker but someone interested in experiencing nature while enjoying and valuing full service. Interestingly, although previously intact landscapes are now boosted with man-made infrastructures like trails, fences, signs, and poles, they still appear pristine and untouched in the eyes of the visitor[16].

Step by step and social cohesion

Tourism has presented new challenges regarding versatility and social cohesion concerning the design and planning of public spaces - where landscapes configure the ultimate space for the public and wildlife. The villages around the coastline have a new role to fulfil as service centres and gateways to the Icelandic wilderness and animal habitats. This role brings about new social and economic potential as well as challenges for municipalities that need to accommodate a growing number of visitors, all while mediating their smooth interaction with nature and wildlife.

When at its best, infrastructure that serves tourism serves the whole society by promoting the well-being and prosperity of the inhabitants. Examples of infrastructure improvements serving both locals and visitors include Borgarfjörður Eystri Visitor Centre. It’s an initiative that grew out of a humble viewing platform in Hafnarhólmi, a summer habitat of puffins, honorary yet temporary inhabitants of Borgarfjörður Eystri, greeted ceremonially upon their arrival in spring. The modest timber platform and stairs have now spun off a 300 m² multifunctional visitor centre that provides a framework for various activities for tourists, fishermen and residents of the village. The visitor centre that was built in concrete came about after the municipality entered into a collaboration with the Architectural Association in formulating goals and emphasis in a competition brief. In fact, design competitions have been increasingly used as a tool to develop popular tourist sites. Examples include Borgarfjörður Eystri and Baugur in the East, Bolafjall in the west and Leiðarhöfði in the south, all projects that are yet to be completed. All these projects have been initiated by small municipalities with the aim to enable access to and enhance experiences in natural environments. A complex and multifaceted endeavour where design competitions are a way for locals, landowners and municipalities of all sizes to engage with professional design communities. Design competition preparations can be facilitated by grants from The Tourist Site Protection Fund. However, they still demand long-term engagement, professional capacity, and funds from the project owner to achieve an ambitious vision, described in a competition brief, through projection.

Since 2018, the majority of projects supported by The Tourist Site Protection Fund have been initiated by locals where the landowner or municipality has coordinated and prepared for planning, design, and construction. In many cases, these are ingenious and well implemented projects while in others further guidance and expertise and even direct involvement of third parties would have been necessary. There is an evident need for applicable tools and access to expertise in design and more aspects of a nature site intervention as well as further financing for construction and maintenance of structures where the project owner can range from an individual, to a large municipality.

Protecting, bathing and weathering

Since ancient times, Icelanders not only swam, they also bathed in geothermal waters from natural sources and created hot tubs to dip in, close to their dwellings. The Guðlaug Baths project derives in part from a rich local ocean-swimming culture in the coastal town Akranes. The baths are nestled in the rocky barrier by the sand beach, which protects the village from the breakwater. As such, the baths form part of a functional protection structure as well as an aesthetical and recreational structure that has made Akranes, a few kilometres off the Ring Road, a worthwhile destination. Another example is Hrunalaug, a historic bathing infrastructure that has shown to be a popular attraction. Located on private property, the owners did not plan for visitors and have faced challenges in protecting the historic infrastructure and its surroundings from harmful intrusion. Hrunalaug is an example of vernacular design, of organic nature, and local materials that need constant mending and maintenance. An overview of the funding allocations shows that many projects receive repeated funding for maintenance and reparations, which raises questions of durability and an eventual need to promote resilient design strategies that take weathering forces better into account.

Durable design for safety and sensation

Since its establishment in 2011, safety has been a top priority for The Tourist Site Protection Fund. Ever since the first rescue squad was formed in Iceland in 1918, following frequent sea accidents and injuries along the shores, Icelandic rescue teams have put themselves on the scales to ensure public safety in Icelandic landscapes. With the increased number of foreign visitors, the volunteers in the Icelandic rescue teams have frequently headed out to help travellers under difficult, even life-threatening circumstances.

Safetravel is a privately initiated and publicly-funded accident prevention project run by Landsbjörg, the Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue. The aim is to provide information to travellers and various services to limit risky behaviour, prevent accidents, and promote safe travel around the country.

Brimketill is a water experience project. An iron platform invites visitors to stand in the gushing waves, promoting safety by keeping visitors away from the slippery rocks. Brimketill is one of many examples of structures designed to respond to a demanding environment. Although the metal structure withstands the waves, the natural path toward the platform needs regular repair and maintenance due to the constant onslaught of the ocean waves, again pointing toward the necessity of robust and resilient structures.

Flexibility for landscapes in constant movement

In a context of constantly changing landscapes with sensational national phenomena like volcanoes and geysers that can gush and erupt when and where no one expects, the flexibility of strategies and structures is essential. Constructed stair at Saxhóll crater in Snæfellsnes and the systemic project hovering trails, which have been installed at Hveradalir (Hot Spring Valley), are both elevated from the ground. The aim is to minimise contact with the ground and protect nature from intrusion. While the stairs at Saxhóll crater can be removed without consderable trace, the hovering trails are designed for movability with a modular design that enables easy disassembly and reassembly. The trails can be adapted to the movements in the landscape, and in the event of an earthquake, the structure is designed to withstand pressure, even if some of the individual pillars might break[17].

Contested notion of access

Previously many coastal areas were only accessible by water. Vast areas of Iceland remain intact, and large parts of the inlands are only accessible during the peak of the summer months. A study from 2013 showed that 43% of Europe’s wilderness is in Iceland (xxx). Currently, there are contested views on whether remote areas in the highlands should be made more accessible for cars or, rather, left in the current state in order to protect them and allow for peaceful visits of hikers. According to the management and protection plan of Vatnajökull National Park, certain areas have been closed for car access, favouring the nature experience of hikers and other visitors.

Location-specific measurements of visitor numbers in Vatnajökull National Park show that the increase in visitors is site-specific within the park. Visits in areas close to road access and facilities increased, while the more remote areas remain reserved for the few[17]. This points toward the importance of site-specific approaches, scalability and a careful approach to each site. Some sites and areas would benefit from more built structures, while others might benefit from initiatives designed to reduce the need for infrastructure. And even removal of infrastructures that ease access to the given spot of the given site.

Network of connected points

One of the assessment criteria of The Tourist Site Protection Fund is the location of a site in relation to the local Destination Management Plan. Coordinated destination management with appropriate design for different sites can limit conflicts between different stakeholders, which is one of the focus areas of the Tourism Balance Sheet when measuring the tolerance limits of the local society.

A growing trend is to approach destinations as points in a network forming circuits that demand holistic design strategies for the assembly of different sites and their spatial and narrative interrelationship. A story that becomes the foundation for the marketing of an area with connected sites. The oldest and most visited circuit is the Golden Circle in southern Iceland, covering about 300 kilometres, with the primary sites Geysir, Gullfoss waterfall and Þingvellir National Park. The Golden Circle had close to 2 million visitors in 2019. Other and more recent circuits are the Diamond Circle in North Iceland, with the primary sites of lake Mývatn, Ásbyrgi Canyon, Dettifoss waterfall in Vatnajökull National Park and Goðafoss waterfall.

The project that received the highest grant from The Tourist Site Protection Fund in 2021 was a network project in the vicinity of the Vatnajökull glacier initiated by Hornafjörður Municipality. A walking and cycling path between Svínafell and the national park in Skaftafell is to be designed and constructed in collaboration between local stakeholders. The so-called glacier route will connect the service and residential core of the area to reuse existing path structures, which will be restored and relinked. The project accords with the destination management plan of South Iceland.

Scalability

The accessibility to different sites on the above-mentioned circuits varies. In the case of the Diamond Circle, Goðafoss waterfall is by the central Ring Road, while some of the attractions inside of Vatnajökull National Park are more remote and have hitherto been accessible only during summer. The expected number of visitors all year round promoted in the destination management plan demands on sturdy infrastructure, which has already been put in place in Goðafoss in accord with local inhabitants. On the other hand, large-scale interventions into the landscapes of Vatnajökull National Park have been contested. The implementation of destination management plans and the launch of marketing campaigns for whole areas must be linked to a more refined design strategy for edge destinations on the circuits that warrant further work. Protection measures for lesser-known hidden gems in the vicinity of the main circuits must be in place before promoting them to a larger audience.

More cross-collaboration is needed

Although there are signs of increased coordination between different agents involved in tourism, future scenarios are often drawn up solely by representatives of a defined tourism industry without involvement of members of the design or art community, nature protection, scholars, and the like. Furthermore, apart from the coordination group for the National Plan for Infrastructure, active between 2019 and 2021, officially established steering groups are often involved in isolated issues. One with a focus on tourism, another on planning and protection of natural and cultural heritage, and a third focused on design. And so forth. Thus, policy and planning work in the realm of tourism in Iceland circulates in an established tourist industry where increased numbers seem to be the principal success criteria, which goes hand in hand with plans put in force in order to limit negative impact on society and environment. In accordance with the Icelandic government’s focus on increasing foreign visitor arrivals, there have been diverse branding initiatives from the official promotional office of Iceland. Many of these initiatives have aimed to extend the travel period around the country, with campaigns instigating winter tourism and distributing visits around the country. However, more coordination is required between those who invite the visitors and those who host and greet the visitors; a plethora of private and public agents that partake in creating links on a chain of infrastructure, facilities and sites that need to be prepared for the influx of visitors all year round. Further, all sustainable tourism should preferably be aimed at and designed for the domestic traveller and the local as well as the foreign visitor, encouraging everyone‘s responsible and enriching engagement with nature, promoting health and quality of life for all.

Collaborating by means of design

Although site-specific conditions demand site-specific solutions, Iceland has been facing challenges that are well-known categorically and have already been dealt with elsewhere. Sharing experience through Nordic collaboration is highly valuable in this respect. A Nordic network could advance the development of a Nordic set of design principles that would form a basis for a Nordic Policy of Design as a tool to promote valuable nature experiences without harmful nature intrusion. However, it is through physical interventions, designed, built and maintained, that we eventually learn. In a quest for sustainable performance of built structures, innovative attitude and state-of the-art knowledge of design should be promoted. Nordic collaboration that facilitates room for experimentation and research on a range of aspects like how design can augment experience of nature by inviting the engagement of the senses, or how design strategies can further robustness against weathering forces, would be valuable.

To increase efficiency and resilience, it is essential to work comprehensively and collectively with more cross-sector, cross-country and cross-border collaboration where design is not end-of-pipe. The potential of design in the context of sustainable tourism lies in part in strategic design. Inherent holistic thinking and aesthetic considerations, the agility and potential of design to create links between lessons from the past and the needs of the future. The applicability of design processes to work with scenarios of movement and human interaction with its surroundings are all methods that can be applied more systematically when it comes to decision-making to prepare for interventions in natural environments. Further, acknowledging that every species has an equal right to thrive on earth, artists, designers, and scholars are paving the way with an empathic and personal approach. Instigating a change from a human-centred to a nature-centred approach. Sustaining sensitive ecosystems by prioritising their protection and regeneration. An essential part of this ideological change, to be followed through in action, is to allow for people’s engagement with and connection to nature. Therefore, design and design strategies that promote and provide tools for responsible engagement with nature is invaluable.

Notes

1 Halldór Björnsson, Bjarni D. Sigurðsson, Brynhildur Davíðsdóttir, Jón Ólafsson, Ólafur S. Ástþórsson, Snjólaug Ólafsdóttir, Trausti Baldursson, Trausti Jónsson. 2018. Loftslagsbreytingar og áhrif þeirra á Íslandi – Skýrsla vísindanefndar um loftslagsbreytingar 2018. Veðurstofa Íslands. https://www.vedur.is/media/loftslag/Skyrsla-loftslagsbreytingar-2018-Vefur-NY.pdf

2 Gunnar Þór Jóhannesson & Katrín Anna Lund. Áfangastaðir í stuttu máli. Háskólaútgáfan & félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands, Reykjavík 2021.

3 Hagstofa Íslands. (2003–2018) Farþegar um Keflavíkurflugvöll eftir ríkisfangi og árum 2003–2018.

https://px.hagstofa.is/pxis/pxweb/is/Atvinnuvegir/Atvinnuvegir__ferdathjonusta__farthegar/SAM0206. px" \h

4 Lög um náttúruvernd nr. 60/2013. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2013060.html

5 Þjóðgarðurinn á Þingvöllum stefnumörkun 2018-2034. https://www.thingvellir.is > um þjóðgarðinn > stefnumörkun Þingvallanefndar > https://www.thingvellir.is/media/1754/a1072-023-u02-stefnumorkun-vefur.pdf

6 Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021.

7 Unesco. https://en.unesco.org/global-geoparks

8 Ibid.

9 Íris Hrund Halldórsdóttir. Ferðaþjónusta á Íslandi og Covid 19. Staða og greining fyrirliggjandi gagna. Ferðamálastofa. 2021. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2021/juli/seigla-i-ferdathjonustu-afangaskyrsla-rmf-juli-2021-m-forsidu.pdf

10 Lög um Framkvæmdasjóð ferðamannastaða 75/2011. https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2011075.html

11 Atvinnuvega- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið. Skýrsla ferðamála-, iðnaðar og nýsköpunarráðherra um stöðu og þróun Framkvæmdasjóðs ferðamannastaða. Atvinnuvega- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið 2021. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/Frettamyndir/2021/januar/210111-atvinnuvegaraduneytid-framkvaemdasjodur-ferdamanna-v6.pdf

12 Atvinnu- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið. Vegvísir í ferðaþjónustu. https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/ferdamalastofa/tolur_utgafur/Skyrslur/vegvisir_2015.pdf

13 Stjórnarráð Íslands. https://www.stjornarradid.is/default.aspx?pageid=0e00328a-0ec4-492b-97f6-f32d41b2fd25#Tab0

14 Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021.

15 Anna María Bogadóttir. “Water as Public Greenspace: A Remotely Urban Perspective on Iceland” in Green Visions: Greenspace Planning and Design in Nordic Cities, Arvinius + Orfeus Publishing, Stockholm 2021.

16 Gunnar Þór Jóhannesson & Katrín Anna Lund. Áfangastaðir í stuttu máli. Háskólaútgáfan & félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands, Reykjavík 2021.

17 Hovering trails. https://www.hoveringtrails.com

18 Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021.

19 Norðurstrandaleið. https://www.arcticcoastway.is/en/about/about

Bibliography

Anna María Bogadóttir. “Water as Public Greenspace: A Remotely Urban Perspective on Iceland” in Green Visions: Greenspace Planning and Design in Nordic Cities, Arvinius + Orfeus Publishing, Stockholm 2021.

Anna Dóra Sæþórsdóttir et al. Þolmörk ferðamennsku í þjóðgarðinum í Skaftafelli. Ferðamálaráð Íslands, Háskóli Íslands, Háskólinn á Akureyri, 2001. Downloaded from: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/files/upload/files/skaftafell.pdf.

Gunnar Þór Jóhannesson & Katrín Anna Lund. Áfangastaðir í stuttu máli. Háskólaútgáfan & félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands, Reykjavík 2021.

Halldór Björnsson, Bjarni D. Sigurðsson, Brynhildur Davíðsdóttir, Jón Ólafsson, Ólafur S. Ástþórssson, Snjólaug Ólafsdóttir, Trausti Baldursson, Trausti Jónsson. 2018. Loftslagsbreytingar og áhrif þeirra á Íslandi – Skýrsla vísindanefndar um loftslagsbreytingar 2018. Veðurstofa Íslands. Downloaded from: https://www.vedur.is/media/loftslag/Skyrsla-loftslagsbreytingar-2018-Vefur-NY.pdf

Íris Hrund Halldórsdóttir. Ferðaþjónusta á Íslandi og Covid 19. Staða og greining fyrirliggjandi gagna. Ferðamálastofa 2021.

Íslensk ferðaþjónusta Samstarfsverkefni KPMG, Ferðamálastofu og Stjórnstöðvar ferðamála — Október 2020 Sviðsmyndir um starfsumhverfi ferðaþjónustunnar á komandi misserum Stjórnstöð ferðamála. Downloaded from: https://home.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/is/pdf/2020/10/Svidsmyndir-um-framtid-ferdathjonustunnar-10-2020.pdf

Landsbankinn. Hlutur ferðaþjónustu í landsframleiðslu í fyrsta sinn meiri en sjávarútvegs [The share of tourism in GDP for the first time greater than fishing industry]. Hagsjá - Þjóðhagsreikningar. Landsbankinn 2018.

Lög um Framkvæmdasjóð ferðamannastaða 75/2011.

Lög um náttúruvernd nr. 60/2013

Snorri Baldursson. Vatnajökulsþjóðgarður, gersemi á heimsvísu. JPV útgáfa 2021.

Vegvísir í ferðaþjónustu. Atvinnuvega- og nýsköpunarráðuneytið og Samtök ferðaþjónustunnar

2015. Downloaded from: https://www.ferdamalastofa.is/static/research/files/vegvisir_2015-pdf

Author information

Anna María Bogadóttir, anna@urbanistan.is

Júlía Brekkan

Júlía Brekkan