By Boris Brorman Jensen

Growing demands for unspoiled nature and a concern for the environment have triggered an increased understanding of nature as a latent tourist resource in Denmark. This evolution together with growth in domestic travel have put design in nature on the forefront. Again, calling for thoughtful design of strategies in order to coordinate the engagement of private and public stakeholders, entrepreneurs and enthusiasts.

Interactive Map

Danish nature and tourism

Scarcity of wild nature in an agri-cultivated country

The Danish climate is temperate and characterised by relatively mild winters and moderately warm summers. Belonging to the deciduous forest zone, the country’s vegetation is relatively poor in diversity compared to other European countries in the same climate zone. With nearly two-thirds of its 42,394 km2 land area occupied by more or less intensive farming, Denmark has become one of the most intensively ‘agri-cultivated’ countries in the world.

Today, only 14% of its total land area is categorised as wild nature, and only 10% is protected by the 2019 Nature Conservation Act §3.[1] Areas protected by Natura 2000 make up 8.3% of the total land area,[2] and only 0.5% is considered ancient forest. With one-third of the 8,750 km of coastline [3] being regarded as unspoilt nature, the country’s proportionately vast coastal landscape is perhaps the nation’s most significant, coherent and accessible natural environment. Denmark does not have the same extensive Right to Roam as other Nordic countries, but the Danish Planning Act safeguards public access along the shoreline.[4] Since no point in Denmark is further than 52 kilometres from the nearest coast, there is a general perception of wide-open and publicly accessible beaches, which may be the most potent image of an unspoiled Danish landscape.

Facts and numbers

Inland, the countryside takes on a more scattered patchwork pattern, but there are also valuable and emblematic landscapes not directly associated with the coastal zone. In 2018, the Danish Environmental Protection Agency initiated a national consultation process that resulted in the nomination of fifteen natural places representing the new so-called National Nature Canon.[5] Four of the fifteen natural sites are situated inland: Suserup Forest in south-western Zealand, Svanninge Hills in the southern part of Funen, the sources of the Gudenå and Skjern rivers on the ridge of central Jutland, and Vind Heath and the Stråsø plantation in the western part of Jutland.

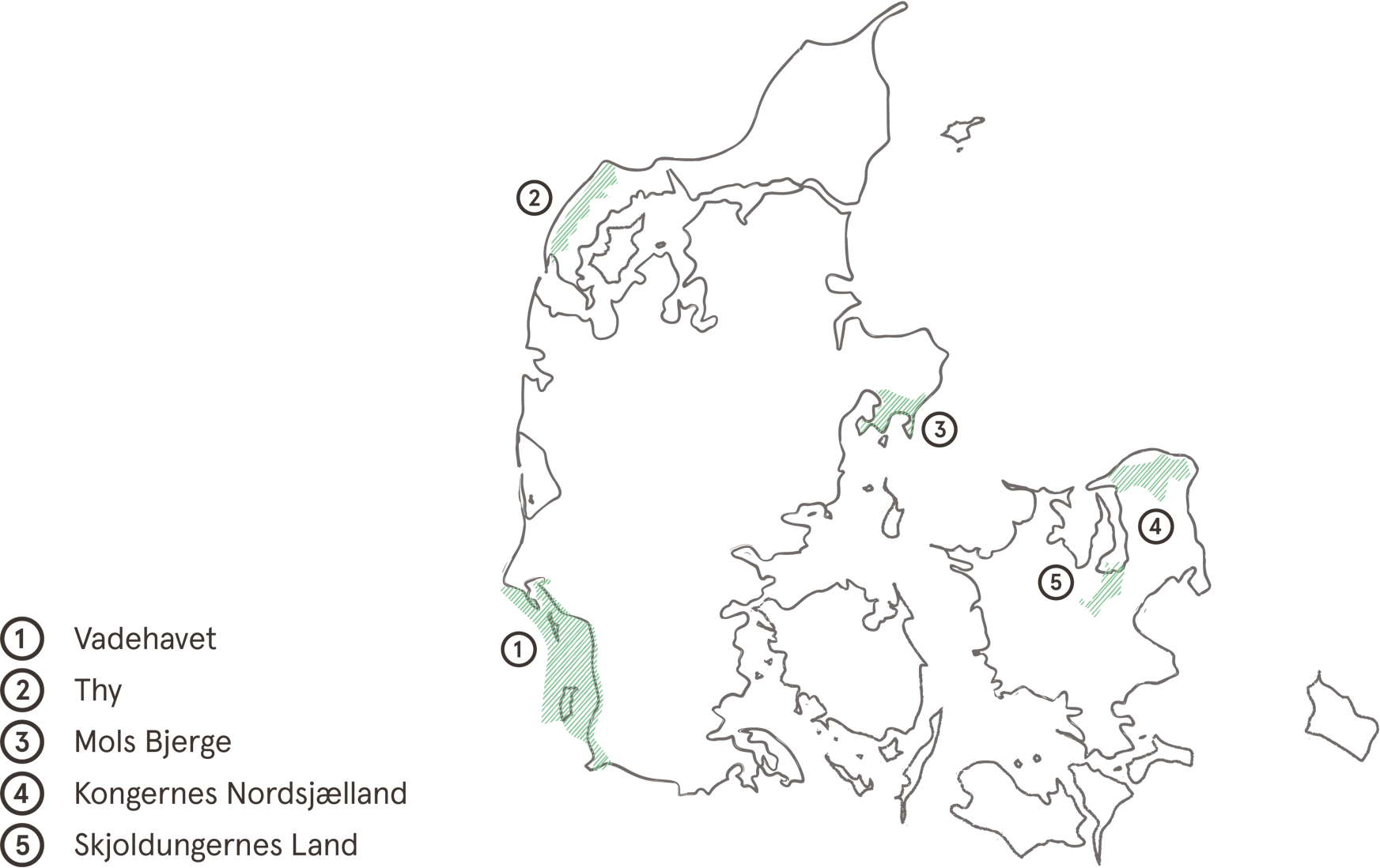

Five national parks also appear on the official list of remarkable Danish natural habitats: Thy in northern Jutland, the Mols Mountains in eastern Jutland, the Wadden Sea in south-western Jutland, the Park of the Kings in north Zealand, and Skjoldungerne Park near Roskilde Fjord. Together, these five national parks cover an area of 2,317 km2, the Wadden Sea being the largest at 1,466 km2. A sixth national park around Skjern River is currently in the planning stage.

National Parks

Contested notions of nature

Statistics concerning the state of the natural environment in Denmark vary according to the source and the definitions applied. Such data is often disputed, as nature conservation and the environmental sustainability of the country’s cultivated landscape have become hot political topics. In 2001, a government council commissioned to prepare national action for increased biodiversity and nature conservation concluded that the quality of Denmark’s natural environment and biodiversity had never before been so poor.[6] It employed a definition of nature that was attacked by a former Minister for the Environment, who claimed that a “field of rapeseed is also nature”.[7] Different political positions fiercely debated whether the vast areas dominated by agriculture should be considered a ‘natural’ part of the Danish landscape.

Another important issue regarding nature policies concerns public access and awareness. Aside from their exceptional natural qualities and unique geological and biological characteristics, all fifteen Nature Canon sites were singled out as they are localities that are easily accessible to the public.[8] Public access and knowledge of Danish nature have become an essential aspect of national conservation policy.

Uncertainty in defining what nature is has raised the question of principle: What is a national park? The five existing National Parks include urbanised areas with supermarkets, industry and farmland. Critical voices claim that these parks are a far cry from the classical definition of a national park, and that they are more like regional brands promoting various business interests. This critique has triggered a response in current proposals by the sitting government to establish fifteen new ‘Nature National Parks’ more strictly targeting nature conservation and wildlife protection.

“In the Nature National Parks, nature must be given the space to be nature. The trees in the forest must be allowed to fall, the water to run more freely, and forestry and agricultural production should not be permitted in such places. At the same time, it should be possible to release larger herbivores, who can take their place in the natural cycle and help establish a wilder nature,” says Minister of the Environment Lea Wermelin, and she continues: “It is a change in nature conservation policy, and it requires us to develop a new set of rules, which provide a better framework for nature and biodiversity. And then I have high expectations that it will generate exciting experiences of nature for Danes”.[2].

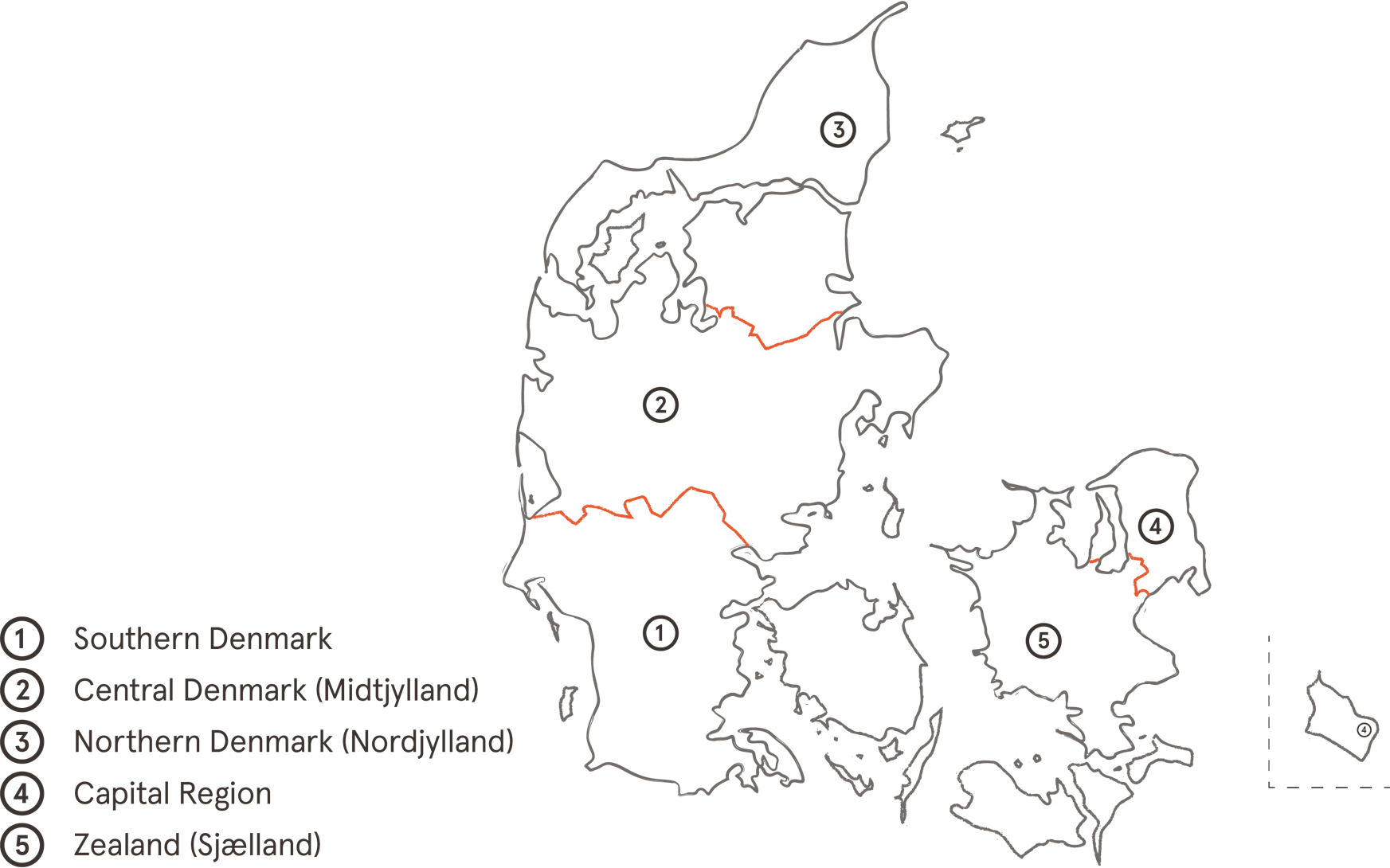

Regions

Danish nature conservation policy

The stated purpose of the first comprehensive Danish nature conservation policy from 2014 is as follows:

“By 2050, Denmark will be a greener country with more diverse nature, and in particular, it will be a country in which internationally protected natural areas, large forests, national parks and the most important habitats for endangered species - including marine environments - will be more coherent.”[9]

Subtitled ‘Our Shared Nature’, the initial environmental policy document focused on three primary target areas:

1) Developing and realising policies for more extended and better interconnected natural environments

2) Strengthening initiatives to benefit wild animals and plants

3) Nurturing a sense of community through the experience of the natural environment and through outdoor activities

Alongside a list of specific government actions and proposals for follow-up municipal planning initiatives, the new environmental legislation introduced a ‘Green Map of Denmark’. This digital map contains the various designated layers of landscape – Natura 2000 sites, national parks, ecological corridors and other existing and future valuable natural habitats – and constitutes a strategic framework and a potential green masterplan for the future of Denmark’s natural environment. The plan was formulated in the 2017 revised Danish Planning Act, which all municipalities are now obliged to contribute to.

The first two areas described in the Danish Nature Policy of 2014 followed up on UN’s and EU’s biodiversity targets for 2020 and marked Denmark’s commitment to its international obligations. The third pledge to strengthen a sense of community through the physical experience of the countryside involves elements of an ideological form of public information-sharing but also has a clear economic rationale.

“Danish nature and the countryside represent one of our most important attractions for tourists and outdoor activities – and this creates thousands of jobs.”[10]

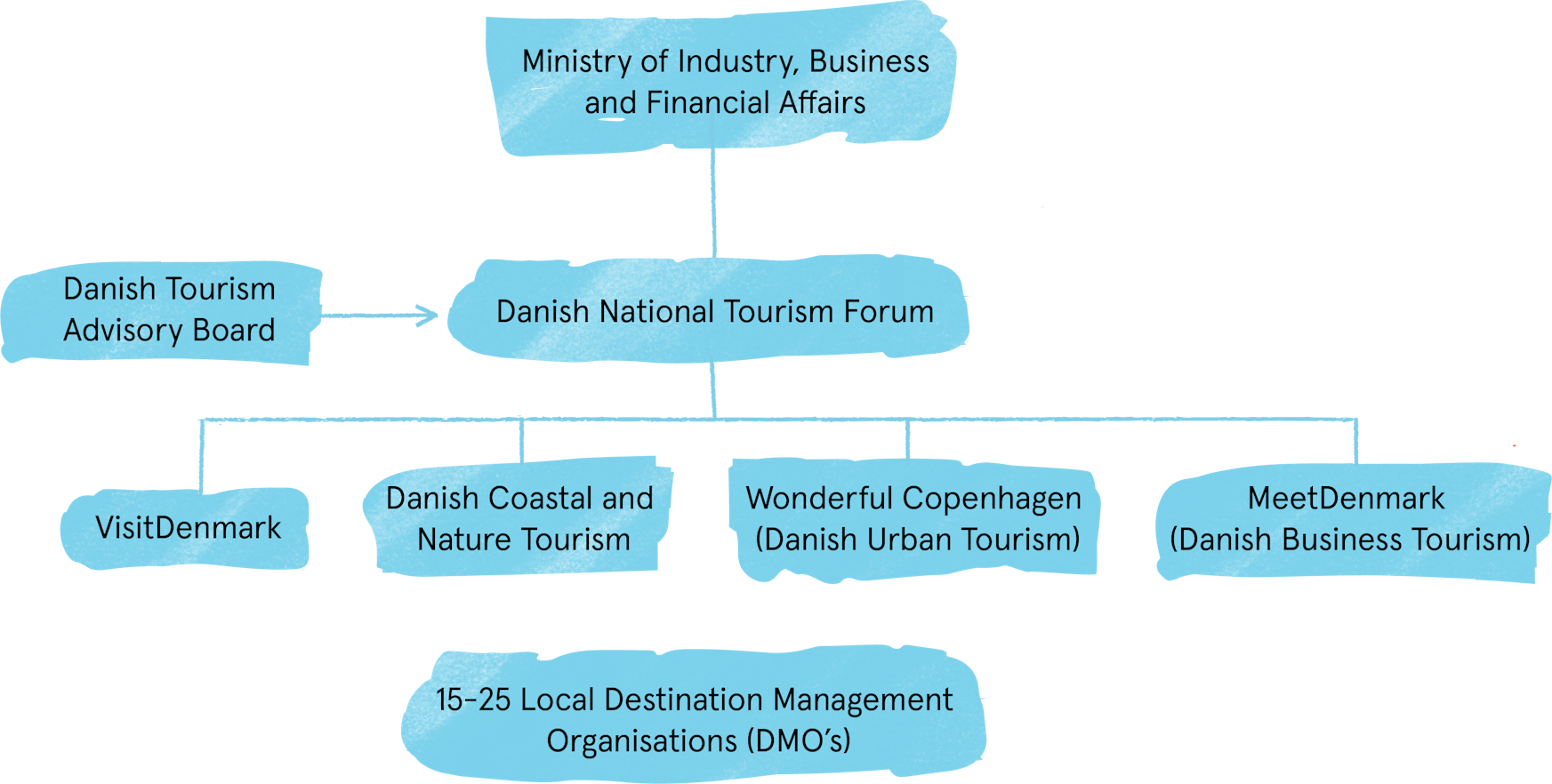

Governance of tourism

Tourism is formally considered an export industry accountable to the Ministry of Industry, Business and Financial Affairs. Its overall policies are organised on two levels; a national and a decentralised level. The National Tourist Forum manages the national level with assistance from the Danish Tourism Advisory Board. Four executive agencies answer to the National Tourist Forum: VisitDenmark (responsible for international promotion), Wonderful Copenhagen (focusing on city tourism), Danish Business Conference Tourism and Danish Coastal and Nature Tourism.[11]

Danish Coastal and Nature Tourism was founded as an independent business fund with its own board in 2015 as part of the government’s plan to grow tourism and the experience economy. Its objective is to develop coastal and nature tourism in Denmark and create a common agenda for their development.

Organisational chart of tourism bodies

Danish Coastal and Nature Tourism also organises the so-called Partnership for West Coast Tourism in collaboration with ten municipalities along the west coast of Jutland. The partnership works to promote more sustainable development in coastal and nature tourism.

“…the west coast should be one of Northern Europe’s most attractive coastal destinations. The west coast should contribute to innovative thinking and create significant growth in coastal and nature tourism and at the same time strengthen the natural qualities and values of the coast.”[12]

The decentralised level of such national policies finds expression in 18 destination management companies (DMCs)[13] organised at a municipal level. Out of the 98 Danish municipalities, 85 are collaborating in one of these DMCs.[3] Most of these companies are partnerships between two to five municipalities promoting specific attractions under a regional brand such as ‘Destination the Wadden Sea’, ‘Destination North Denmark’ or ‘Destination Limfjord’.

Important NGOs

Planning for the agricultural, environmental, and recreational use of so-called ‘open land’[14] in Denmark is a frequent topic in the planning debate. The perceived conflict between the determination to continue large-scale industrial farming and concerns for declining biodiversity and the general so-called ‘ecological condition’ of the existing countryside is currently the subject of heated discussion.

Another less controversial but nevertheless potentially divisive question regards the growing interest shown by various representatives of the experience economy in this ‘open land’ and its natural resources. Municipalities that derive substantial financial benefit from tourists holidaying in summerhouse areas are fighting against state planning of local fish farms to protect their Blue Flag beaches[15]. Private tour operators marketing exclusive fishing trips are pushing for access to protected nature areas; investors in luxury retreats and spas are lobbying to deregulate or bend the strict Danish Coast Protection Act. This means that there is increasing friction between the agroindustry, the tourist sector and bodies working to protect the countryside.

And these are not always simply conflicts rooted in economics or business; they might involve Sunday morning mountain bikers unknowingly trespassing on private forestry rights, triggering intense local clashes. With only 14% of the total land area being defined as unspoiled nature and with no comprehensive Right to Roam, very little of the Danish countryside can be considered a truly ‘shared space’. There is always some kind of dominant interest determining decision-making. Even small non-commercial communities tend to organise in separate associations fighting for their particular interests: hunters and fishermen, ornithologists, hiking associations, etc.

The Danish Outdoor Council [16] is a leading agent in the attempt to bridge the gaps between opposing interests. Its 86 individual association members are organised in an umbrella structure. The council,

“works to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to benefit from outdoor activities in prosperous natural environments. We do this through political advocacy, by supporting specific projects and by bringing together interested parties and by supporting communities working to promote outdoor life.”[17]

But even these well-meaning efforts to protect the best interests of the natural environment and to share its amenities fairly for the benefit of public health are frequently up against strong opposition from leading farming organisations. These organisations represent a highly specialised industry, poorly equipped to develop potential recreational side-effects of its high-efficiency and often monofunctional production methods. This conflict of interests can be seen as a clash between orthodox industrial thinking and newer emerging multipurpose practices of the post-industrial experience economy.

Another influential NGO is the Danish Society for Nature Conservation (DNC). With 130,000 members and 1,500 volunteers, DNC is not only the biggest member organisation in Denmark but also the only NGO in Denmark with the right to raise conservation issues. Established in 1925, DNC has a commitment “to conserve and protect the natural environment in Denmark in order to secure a future where natural forests and meadows rich in biological diversity still exist and clean drinking water is still obtainable.”[18]

This broadly supported and well-established watchdog is not afraid of political controversy and has often spearheaded breakthroughs in environmental policy and action. For example, ten years before the Government launched the idea of the Green Map as part of the first National Nature Policy, DNC published a detailed map of the ‘Future Landscape of Denmark’, anticipating current efforts to make a masterplan for Danish nature.[19]

At the beginning of 2021, in collaboration with researchers from Aarhus University, DNC published a national Nature Capital Index [20] ranking all 98 Danish municipalities. It was far from good news for all of them. Ranging on a scale from 0-100 according to biodiversity score, many urbanised municipalities were shown to have higher biodiversity than many rural municipalities. The city of Silkeborg, which brands itself as Denmark’s Outdoor Capital, is ranked number 13 out of 98 municipalities with a Nature Capital Index of only 43 out of 100. The island of Fanø off the west coast scored highest with a Nature Capital Index of 87.

Being the most influential environmental watchdog in Denmark, DNC is often up against the powerful Danish Agriculture & Food Council, representing the agroindustry. A turning point in the ongoing conflict of interests was in 2019 when the two organisations agreed to allow 100,000 hectares of farmland to revert to some form of natural state. This agreement was interpreted as possibly signalling the beginning of a new era of collaboration between the two notorious adversaries. A new alliance was formed by external demands to reduce the agroindustry’s growing percentage of the total Danish CO2 emission.

Coastal and nature tourism

According to Statistics Denmark, the number of foreign visitors in Denmark has grown by 30% over the last decade, making the Danish tourist industry responsible for 4.6% of the country’s national export [21]. Since 2008, Denmark has accounted for around 45% of total overnight stays in the Nordic Countries [22]. Almost 170,000 people [23] are currently employed in the Danish tourism industry, mainly outside the largest cities. The most significant segment of the industry is the coastal and nature tourism branch, defined as tourism outside the four main cities: Copenhagen, Aarhus, Odense and Aalborg.

According to VisitDenmark, the net turnover from national and foreign visits to the Danish coastline and its scattered patches of natural hinterland amounts to more than €8.5 billion annually. Coastal and nature tourism accounted for more than 70% of the total of 56 million registered overnight stays in 2019. Close to half of these overnight stays are domestic, making tourism more than just an export venture. Coastal and nature tourism are an integrated part of the growing Danish experience economy and have become important economic drivers in many coastal municipalities [24], which typically lag behind in terms of economic growth compared to the more urban regions and larger cities.

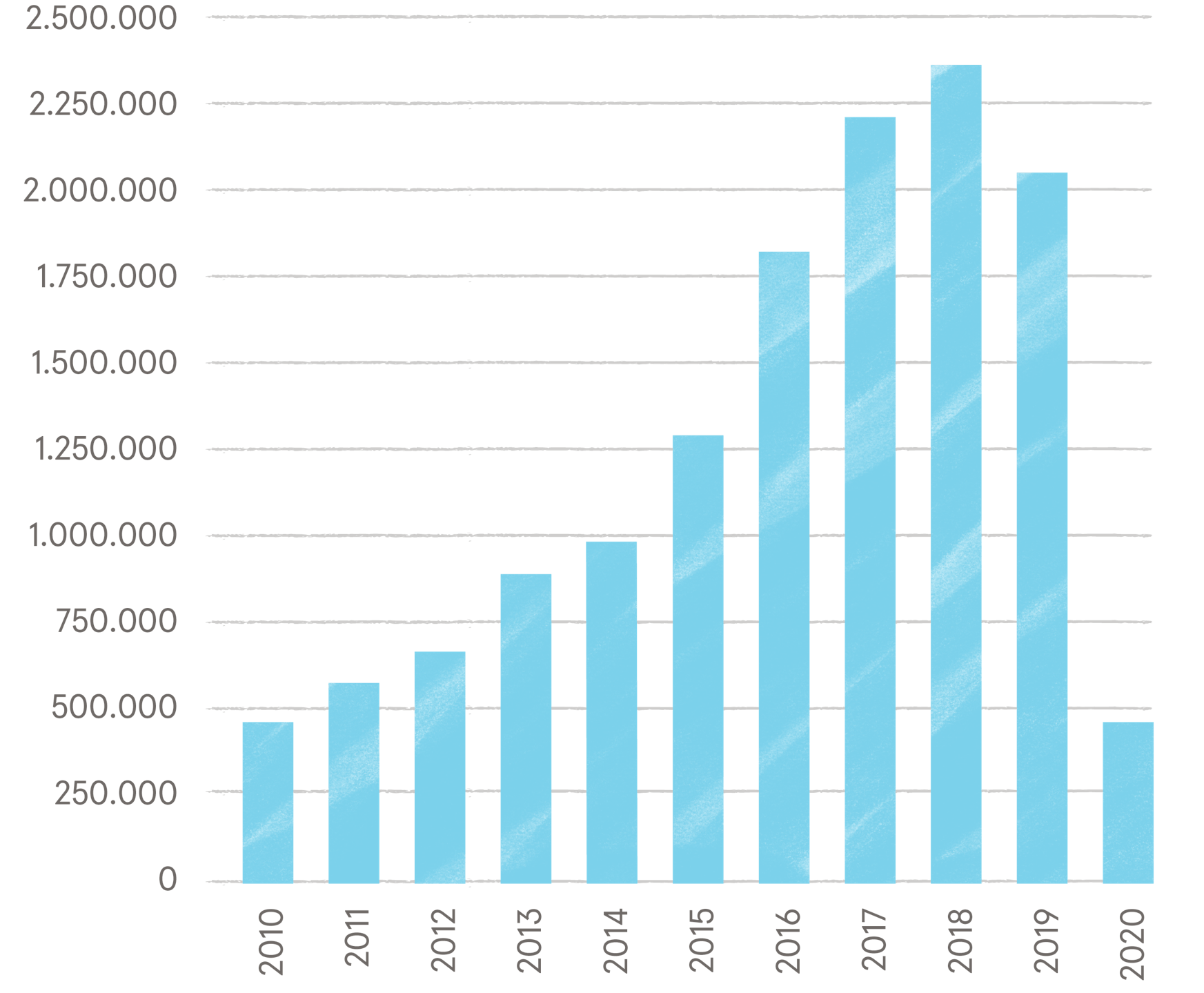

Development of Tourism

Not all 8,750 kilometres of the Danish coastline are being marketed as a prime destination for tourism and domestic recreation. Still, coastal tourism is undoubtedly the mainstay of the tourist sector. With the second-lowest percentage of so-called ‘good preserved’ nature in the EU [25], most potential inland tourist destinations – forests, rivers, marshland, moor and other pristine landscapes – appear to be too scattered or too isolated to be promoted for tourism on the same scale as the west coast of Jutland.

Growing demands for more unspoiled nature and a general concern for the environment have thus triggered an increased understanding of nature as a latent tourist resource. VisitDenmark and the Danish Nature Agency have made bucket lists of Denmark’s most beautiful places featuring natural highlights like the five national parks. Most tourist and leisure attractions in the category of ‘nature’ or ‘the great outdoors’ are near existing summerhouse areas and benefit from existing infrastructure and services. While coastal tourism has become an extension of the export economy, these inland pockets of more or less unspoiled nature seem to cater to a more domestic type of tourism, a subsector within the tourism industry that has seen a dramatic boost during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dynamics between public and private players

The strategic development of localised environmental potential within tourism, regardless of whether the potential is ‘cultural’ or ‘natural’ or whether it is linked to coastal areas or inland nature, demands careful planning and coordination between many actors.

Even though the planning authority clearly lies with the local municipality, cooperation between public authorities, private stakeholders, and commercial actors has become a central aspect of current coastal and nature tourist development strategies. The Danish Planning Act ensures public participation in planning processes, and top-down decisions have a history of miscarrying when applied to large-scale nature conservation efforts [26]. In addition, many of the boldest and most visionary projects are often initiated by local entrepreneurs and enthusiasts – people with hands-on knowledge about opportunities for local development. The municipality often adopts a coordinating and facilitating role in such a bottom-up process.

Many coastal municipalities engaging in projects combining nature restoration and tourist development have a relatively small population and limited budgets, making them dependent on external funding. Some critical voices even question who is really in charge of bottom-up projects; the community of committed activists and local entrepreneurs initiating the projects, the democratically controlled municipal planning authorities, or the private foundations providing financial backing. It is beyond the scope of this report to discuss the influence of private philanthropy on democratic processes and development strategies – but it is a fact that private foundations in Denmark play a vital role.

One of the principal private players in this new strategic model is the philanthropic association Realdania [27]. Providing annual donations of up to €100 million, it sponsors pioneering projects in the current effort to stimulate the development of peripheral regions and offers financial support for site-specific assets, landscape qualities and other local resources. This support has taken the form of philanthropic programmes such as Place matters, Land of Opportunities and Partnership for west coast tourism.

Realdania primarily supports what has been termed the ‘built environment’. Other foundations, such as the Nordea Foundation, support a more qualitative approach to coastal and nature tourism by linking access to nature with various efforts to support physical and cultural activity and promote public health measures. The Nordea Foundation offers several strategic funding programmes, for example, Curious about Nature and More Call for the Open Air. A recent project, Poetic Ways, represents one of many new strategies using narrative as an infrastructure imposed on the landscape, combining existing topographies with novel designed elements. Other large private foundations like TrygFonden, the A.P. Moller Foundation, the Carlsberg Foundation and Aage V. Jensen’s Nature Foundation are significant players, donating between them hundreds of millions of euros to similar strategic initiatives every year.

Another privately funded project included in the compilation is the arrival and access facility at Mønsted Limestone Cave, designed by Schønherr Landscape Architects. Sponsored by the Bevica Foundation, which strives to make sites of both natural and cultural interest accessible “for people with mobility impairments by working with others and against the background of current societal issues.”[28] Other such current societal issues are often part of the philanthropic agenda.

Mønsted Limestone Cave, Schønherr Landscape Architects

Carsten Ingemann

Carsten Ingemann

A shift in the mechanics of nature exploitation

Proximity to the sea may once have been the key strategic consideration for the fishing industry and related secondary trades. Now, clean, white and relatively uncrowded beaches are the in-demand commodity offered and promoted by the growing tourist industry. With its strong links to steadily increasing urbanisation, it is hardly surprising that this tertiary sector’s marketing of nature experiences comes with a set of requirements associated with more urban lifestyles.

It is equally evident that this gradual shift in the mechanics underlying the exploitation of the natural environment has triggered a new set of economic development strategies. This shift received its first impetus in the 1920s when industrial workers won the right to two weeks of vacation. The subsequent establishment and later expansion of geographical zones dedicated to summerhouses with their own particular set of planning and design regulations peaked in the 1960s, when the majority of Danish summerhouses were built.

Several environmental protection organisations are now calling for regulation in this area. Their demands are triggered by concerns about apparent tendencies towards suburbanisation of summerhouse zones, boosted by increasing demand for larger and more luxurious summer cottages with ‘all-year standards’. While the first wave of this recreational summerhouse architecture is now celebrated in some quarters as part of folk culture, the current wave of strategic design interventions to stage, promote and explore the tourist potential of nature through different and more hybrid kinds of experience economy programmes is still in a sort of pioneering phase.

Such architectural concerns reflect mounting demands for more sustainable coastal and nature tourism strategies. Increased focus on local integration based on differentiated site-specific or so-called ‘place-bound qualities’ is beginning to define a new path forward. There is simultaneously a growing insistence that tourist development strategies bring more direct benefits to small and remote communities without eroding those fragile qualities that are the very foundation of their tourist appeal.

The aim of nature protection in itself is not, of course, to boost tourism. However, several initiatives have been launched by public authorities, civic organisations and private foundations seeking possible synergies between tourism and some kind of intended nature conservation efforts. Danish planning regulations for ‘open land’ outside urbanised areas and conservation zones are quite complex. Erecting buildings for purposes of tourism, even small structures such as viewing platforms, close to listed areas or areas designated unspoilt nature, is very difficult if not entirely impossible [29]. EU Nature Directives are playing an increasing role in decentralised planning processes, and the basic thrust of the existing Danish Planning Act is to protect ‘open land’ from urbanisation [30]. However, some approaches are taken by central planning authorities to bridge the principal conflict of interests between the protection and development of the great outdoors. For example, the Danish Nature Agency has published a set of general guidelines to assist municipal authorities and local tour operators in accommodating the request for more differentiated coastal and nature development strategies.

Another critical aspect is the seasonal variation in the number of visitors. The high season during July and August attracts more than one-third of all visitors (both foreign and domestic). There are attempts to incorporate the three adjoining months, known as the ‘shoulder seasons’, of March-June and September-October. Danish summers are notoriously fickle for sun-loving people, so various strategies are being formulated to supplement the traditional high season, packaging cultural experiences supported by urban-style amenities such as safe tracks, welcoming rest areas and other backup facilities – boardwalks, information graphics, parking facilities, easily accessible viewpoints, shelters or larger structures like visitor centres and museums.

While it might look like a reasonably elementary shift in the mechanics of exploiting nature; from extracting matter and organic material for utilisation to implanting designed elements, networks of narratives and other operating devices of the experience economy, the process opens up a Pandora’s box of issues and conflicts demanding a whole new set of planning regulations, procedures and instruments. It also sets the scene for a change in the overall spatial management of the countryside with opportunities to convert old farmland into new natural environments. Prospects open up for a new planning paradigm with opportunities to use design intervention strategies as a vehicle for nature protection. Various attempts to make the general public aware of the unique qualities of the Danish countryside by providing better access and securing sites for wildlife observation that do not disturb or erode the very qualities that make them unique. This involves a strategy for designing nature that also supports existing public health policies. Science tells us that easy access to green areas improves people’s health. The countryside can be equally as rich as natural habitat and as a resource for human health and recreation. It can be tended and cared for with multiple interests in mind. The planning challenge is, of course, to design a sustainable interface between various human activities and the ecological balance of nature.

Design traditions and local craftmanship

Initiatives promoting access and activity

Design initiatives to make the Danish countryside more accessible and supplement outdoor adventure experiences with more or less curated services come in various types representing a range of tactical approaches – from primitive footpaths and modest shelters to spectacular visitor centres and site installations or monuments considered important national landmarks. Designs can be scaled up – or down – to allow a more or less deliberately staged nature experience. Some facilities have a clear physical presence, such as a boardwalk meandering through a wetland or a ‘starchitect’ designed visitor centre with dedicated exhibition space, gourmet café and regulated parking. Some interventions are more ephemeral, like the comprehensive system of different coloured spots on trees and signposts marking various routes in the landscape. Some have no physical design component at all. Finally, many strategies simply use narratives to connect existing points and places on a mental map, such as the Poetic Ways or Pathways into the Past, combining access to nature with public health or education interests [31]. The best-known of these narrative constructions is the 4,218 km long Marguerite Route, connecting areas of outstanding natural beauty and picturesque spots with cultural monuments and historical sites spread across Denmark.

Another important family of narrative trajectories leading through the Danish landscape is the pilgrim route in its various guises. These are not always religious in character but comprise a series of culturally curated walks through the countryside, such as the 175 km Camønoen running around the island of Møn, branded as the “friendliest hike in the kingdom of Denmark” [32]. Several historic footpaths and trails through the country have also been recently upgraded with new signage, rest areas and a ‘reinforced narrative’. Examples are The Ancient Road running all the way from the northern part of Jutland to Germany, or The Old Towpath running 70 km along the River Gudenå in eastern Jutland.

Basic design typologies

It is difficult to point to any specific Danish design tradition or prevalent craftsmanship applicable to the range of methods and tactics used to signal or enable access to outdoor experiences. The Danish Nature Agency has made an online guide to 170 state-sponsored nature areas commonly equipped with a system of signed pathways and parking areas. The Nature Agency uses dark red signposts as their signature, but there are no common standards, and the diverse systems of coloured signs used by various municipalities and private associations can be quite confusing. Many state-owned nature reserves have picnic areas with standard benches, tables and primitive toilet facilities. Robust and humble is probably the most appropriate characterisation of these facilities.

It is not legal to camp at most of these basic picnicking sites, but there are plenty of shelter sites spread all over the country. According to The Outdoor Council [33] there are approximately 1,500 primitive shelters in Denmark, which can be used overnight without charge or booked online for a symbolic fee. Most of these shelter-cum-campfire sites have a standard layout equipped with generic and robust timber constructions. However, some are more sophisticated, with designs suggestive of the Stone Age, Viking times or are variations of the more luxurious glamping typology which is becoming more and more popular. Included in the compilation is an example of a shelter camp at the southern tip of Funen designed by an architect. Modest but comfortable and somewhat playful in its expression, the Millinge Klint shelter camp represents an emerging design strategy providing simple luxury and catering to a much broader audience than the hardened scout or camper.

The architecture of Summerland parks

The architecture of so-called ‘Summerland parks’ [34] has its own distinct architectural history and has come under increasing demands for conservation. The majority of summerhouses built for ordinary folk since the beginning of the 20th century are quite modest and represent an idea of summer vacation and free time as a humble and natural alternative to working life.

Most of the summerhouses built prior to the 20th century were situated in the landscape as solitary elements. The first vacation village for ordinary people was Eigil Fischer’s Vacation Village, planned at the beginning of the 1920s at Femmøller Beach near Ebeltoft. Designed as a baroque-style park with shared facilities such as a small stadium, a cultural green space, and a main street with shops, the innovative vacation village transmitted the ideal of an elemental, pastoral life conveyed through architectural simplicity.

After the adoption of the Danish Holiday Act in 1938, a cooperative association called Danish Folk Vacation, formed by a workers’ union, built several vacation villages around the country. Over the years, they became more and more ‘modern’ in their design, and today, most new summerhouses do not lack any of the conveniences associated with most people’s everyday life. More affluent segments of the population seem to be looking for ever more luxurious versions of nature vacation resorts. This demand for more refined and extreme experiences of or in the natural environment requires more distinct and expressive designs. An emergent demand for ‘quality experience’ or ‘uniqueness’ is also reflected in many other contemporary design-in-nature initiatives – and a growing focus on safety and concern for environmental impact.

Current designs and visions

Current Trends

Increasing public engagement in environmental issues and the accompanying interest in nature and authentic outdoor experiences have triggered a wave of new projects to bring the sparseness of the natural environment more clearly into focus and make it more accessible. Within weeks of its opening, the newly established 12 km ‘Silk Route’ through some of the beautiful landscapes around the town of Silkeborg has provided an extremely popular weekend outing for locals and visitors alike. The Forest Tower at Gisselfeld has attracted 350,000 people from 74 different countries within a year of opening. These curated initiatives designed to enrich and exploit the natural environment have become a new way to trigger local development, and many private foundations, municipalities, public associations and tourist organisations are eager to step in with support. This tendency also seems to cause a shift in the dominant design paradigm. The former simplistic and reserved approach to installations of cultural artefacts in nature has shifted to a much more visually up-front and sometimes even spectacular expression – as in the Forest Tower, for example. A new generation of shelters with carefully designed elements has entered the scene. The former generic heavy-duty lumber constructions inhabiting the country’s public nature areas are slowly being upgraded to more delicate structures in weathered steel, glass and concrete. Previous picnic sites, neutral in their design, have become explicit cultural markers, and a new and evolving infrastructure of visitor sites is beginning to frame the great outdoors.

Overall case selection criteria

The design initiatives mentioned above represent a wide range in scale, scope, tactics and ownership. Some are part of a nationwide system of publicly accessible facilities. Some are privately owned and commercially operated local attractions. Some are deliberately designed as autonomous attractions, and some function as relatively anonymous and supportive forms of service infrastructure. To provide an illustrative group of contemporary examples representing the varied range of design tactics and typologies, five categories are suggested as overall selection criteria: Place, Site, Landmark, Path and Park.

‘Place’ here is defined as a location in the landscape that has developed gradually, such as a viewing point visited for centuries, which over the years has been equipped with design elements such as steps, rails, signposts, benches etc. The concept of a ‘site’, on the other hand, indicates a more deliberate planning action and an attempt to shape or create a specific image of a place through design and marketing strategies. The Sunset Plaza in the town of Skagen included in the compilation is an example of a ‘place project’. Skagen had a long tradition, nurtured by locals and tourists, of gathering on the beach to watch the sunset. The project designed by landscape architect Kristine Jensen was intended to sustain this existing tradition, not to initiate it. On the other hand, the Forest Tower project, designed by EFFEKT Architects, is a characteristic example of a ‘site project’. The tower was built to attract people to a commercially operated adventure camp and quickly became a design(ed) destination in its own right. The distinction between place and site resembles the distinction within planning theories between ‘placemaking’ and ‘place-making’ [35]. The two categories are defined as ends on a continuum. In practice, however, there will be many overlaps.

With its impressive 45 metre spiralling and gracious structure, the Forest Tower has an unmistakably monumental character. However, the category ‘landmark’ introduced here has a different set of connotations. A ‘landmark project’ defines a set of design initiatives that give access to historical monuments. A landmark project emphasises an existing relationship between a landscape and a set of distinct cultural traces. The improved arrival facilities and new inner stairways at Kalø Castle Ruin designed by MAP Architects – also included in the compilation – is an example of a landmark project. The delicately designed stairway inhabits an existing monument and, at the same time, provides the visitor with a view of the natural and manmade landscape in which the ruin is embedded. A landmark project does not have to be monumental. The category is meant to underscore design strategies that provide a better understanding of the ancient link between human artefacts and a particular landscape. The set of physical interventions that allow access to the source of the largest river in Denmark and the small stone with the carved message: The Source of the river Gudenå are not monumental at all – but in this context are considered a landmark project. The discrete signs and pathways provide access to a place that has been the home of religious and cult practices since the Bronze Age. The landmark category takes into account the fact that humans have engraved nature with cultural significance for millennia. The landmark projects included in the compilation are all examples of new design interventions somehow trying to rediscover or highlight these historic ties.

The category ‘path’ includes all the above-mentioned narrative strategies, such as the Marguerite Route and Camønoen, as well as the physically revitalised Ancient Road (Hærvejen) and other pathways making nature and cultivated landscapes accessible. Path is a fairly broad category but does not include projects like the Forest Tower, even though the project in principle is a pathway in the sky. The category attempts to sort the selected examples after their predominant character. Path projects can be a round trip, and the physical presence of their distinct elements can be monumental. In this context, the Forest Tower is regarded as a tourist development project rather than a piece of connective infrastructure – and is thus not included in the path category.

The category of ‘park’ includes attempts to fence or delimit a particular natural habitat or landscape. The five Danish national parks and their respective visitor centres and systems of information are obvious examples. Even the fifteen recently proposed Nature National Parks will come with more or less explicitly designed information points and thereby belong in this category. The stipulation of a park can be physical or symbolic, with a real or imagined line defining the inside and the outside of an area and indicating designated access points or gateways. The Filsø visitor centre designed by Schønherr Landscape Architects is an example of such a project, establishing an access point to a newly re-established natural landscape.

Challenges and future prospects

The wave of design-in-nature projects presented above represents a novel way to trigger local development, serving as a key device for communicating and mediating nature experiences. A new planning recipe mixing nature conservation, local development, public health, education, and sustainable tourism seems to be born. But many obstacles are yet to be confronted in the form of complex planning issues, legal struggles, and environmental concerns that will doubtlessly be raised in the near future, giving rise to many difficult questions.

Will the sparse remnants of untouched Danish nature be invaded by a new generation of ‘Instagrammable’ projects representing an ever-expanding experience economy? Where are the no-goes in this new colonisation of nature? Is there a way to pursue, develop and refine the low-impact and more humble design tradition of the past? Or is this historical tradition of simplicity no more than a bygone relic of relative poverty that only needs to be superseded? Will the lush new landscapes and visitor centres replace traditional farms and land used for food production? Which landscapes deserve to be promoted through viewing platforms and infographics? Is this eagerness to frame and encapsulate our experience of nature and the cultural landscapes alienating us from any authentic and non-commercial involvement with the ‘natural’ world?

The question is who decides where nature should be engaged and marketed through design. Is it the private foundations, the state and municipal authorities, or the local communities? Before entering into an active partnership, most private foundations demand co-funding from municipalities to ensure local commitment and a bottom-up legitimacy for their support. But there are two key questions: Who is really in charge? And who benefits from the projects? Is it the well-organised, resourceful, and wealthy municipalities that can raise the seed money? Or is it the small and often less affluent municipalities that are in greater need of financial support but might have difficulties raising the initial investment required for co-funding? These are some of the essential political and cultural questions regarding future investments in Nordic design in nature.

Author information

Boris Brorman Jenssen, architect MAA, PhD

bbj@borisbrorman.dk