By Knut Bang

With its vast coastline and deep fjords, high mountains, and extensive woodlands, Norwegian nature has traditionally been available for everyone to enjoy. Still, it is protected by strict laws and regulations thanks to pioneering environmental governance. Norway’s equality-based society and the state’s significant investments in infrastructure and design have undoubtedly helped make nature more accessible for an outdoor-loving population.

Until the pandemic put travel to a halt in 2020, the Norwegian tourist industry was experiencing steady growth but also signs of over-tourism. As the industry is preparing to rebuild, visitor management and sustainability are key to finding the right balance between offering great experiences and protecting fragile nature and communities. More and more visitors seek unique nature experiences and green destinations. Design thinking, innovative architecture and electrification of travel are part of the Norwegian future of tourism.

Interactive Map

Norwegian nature and tourism

Deep fjords and high mountains

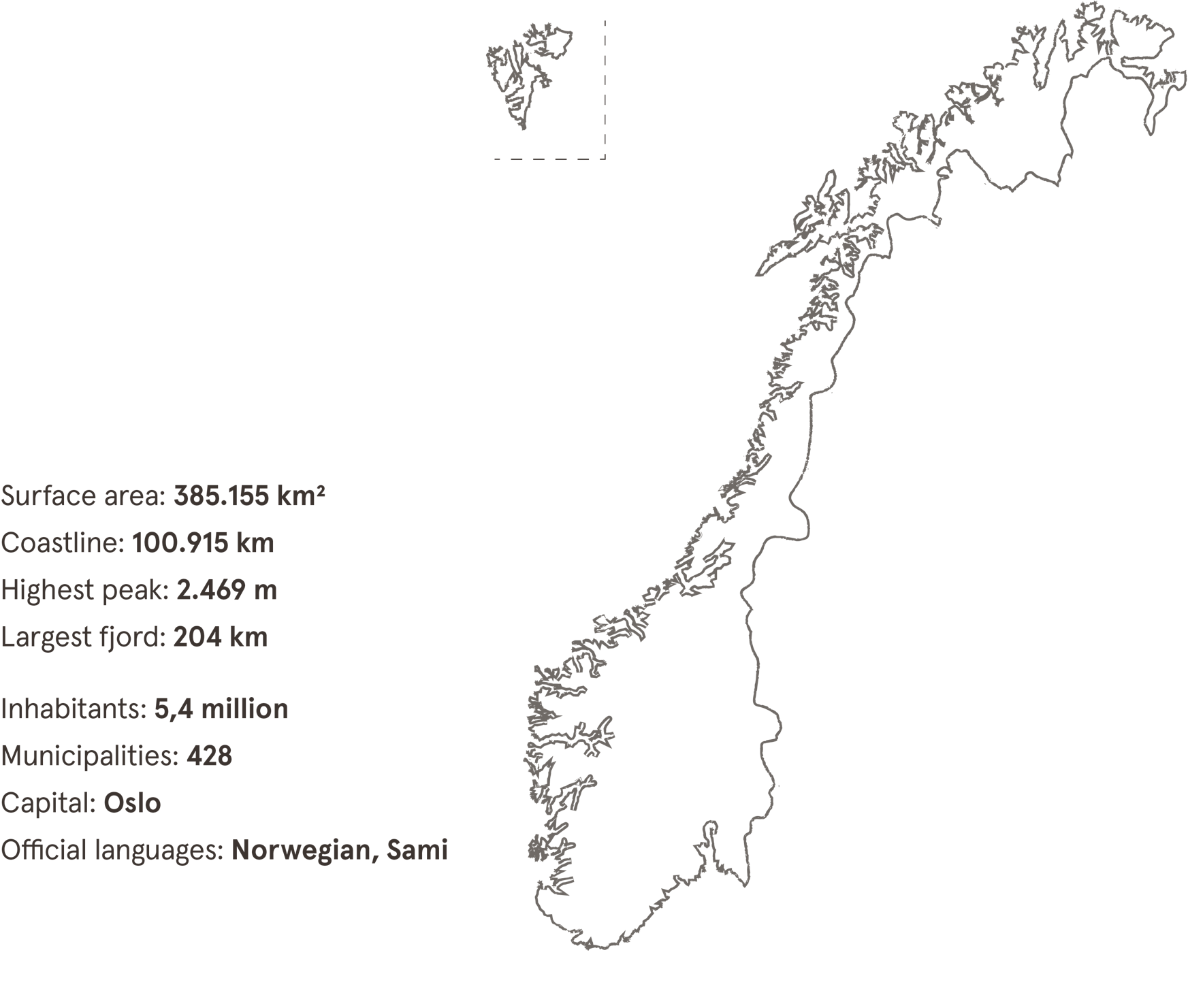

The Kingdom of Norway comprises mainland Norway, the archipelago of Svalbard, and the remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen, totalling a surface area of 384,484 km2 [1]. Mainland Norway’s long and rugged coastline stretches across 100,915 kilometres along the North Sea and is scattered with deep fjords and thousands of islands. Much of the country is dominated by mountains and rocky terrain with subarctic and tundra climates. A vast range of dramatic features have been created by prehistoric glaciers which carved deep grooves into the land. Today, we can see the traces of this in our steep fjords on the west and north coast.

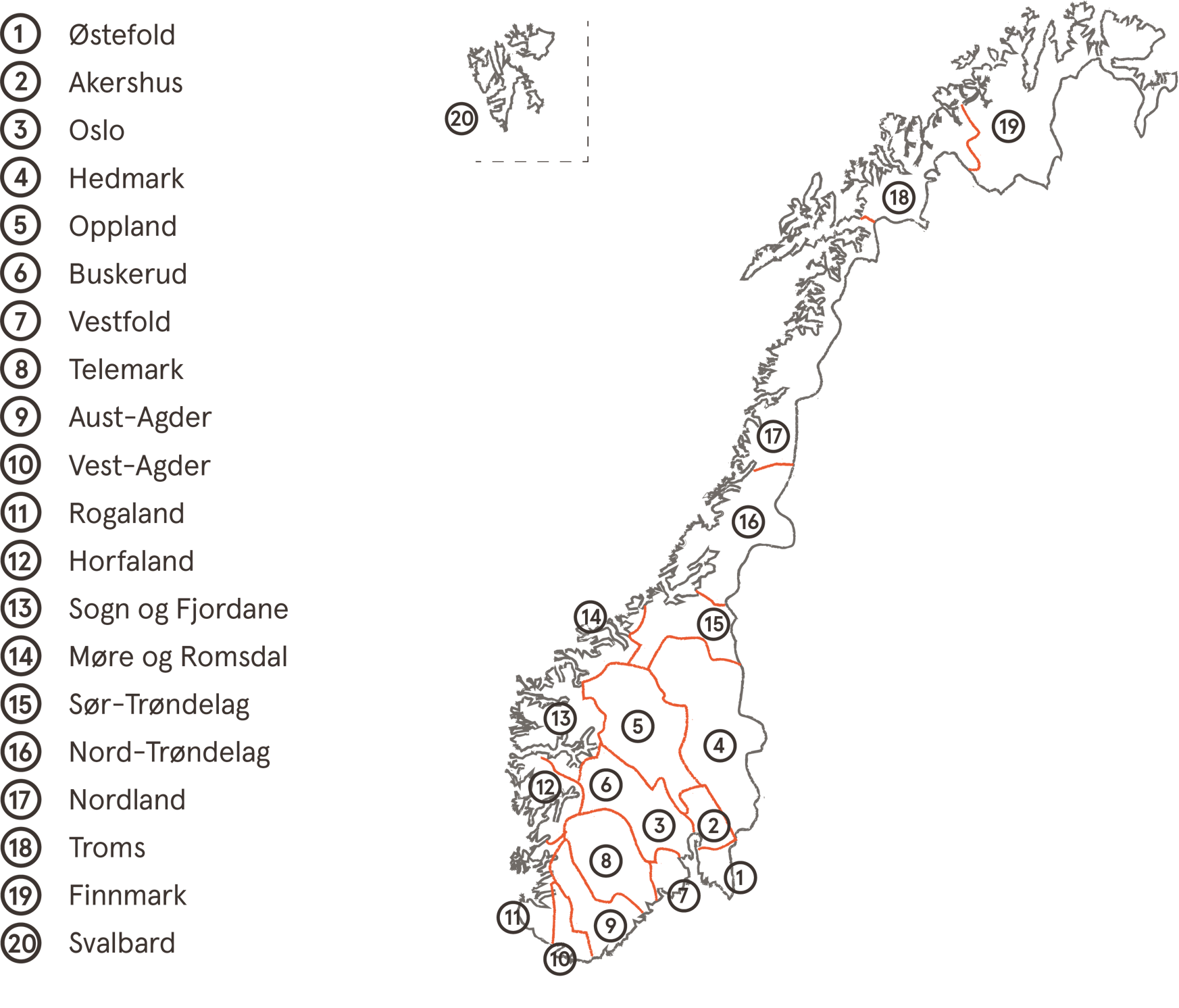

Regions

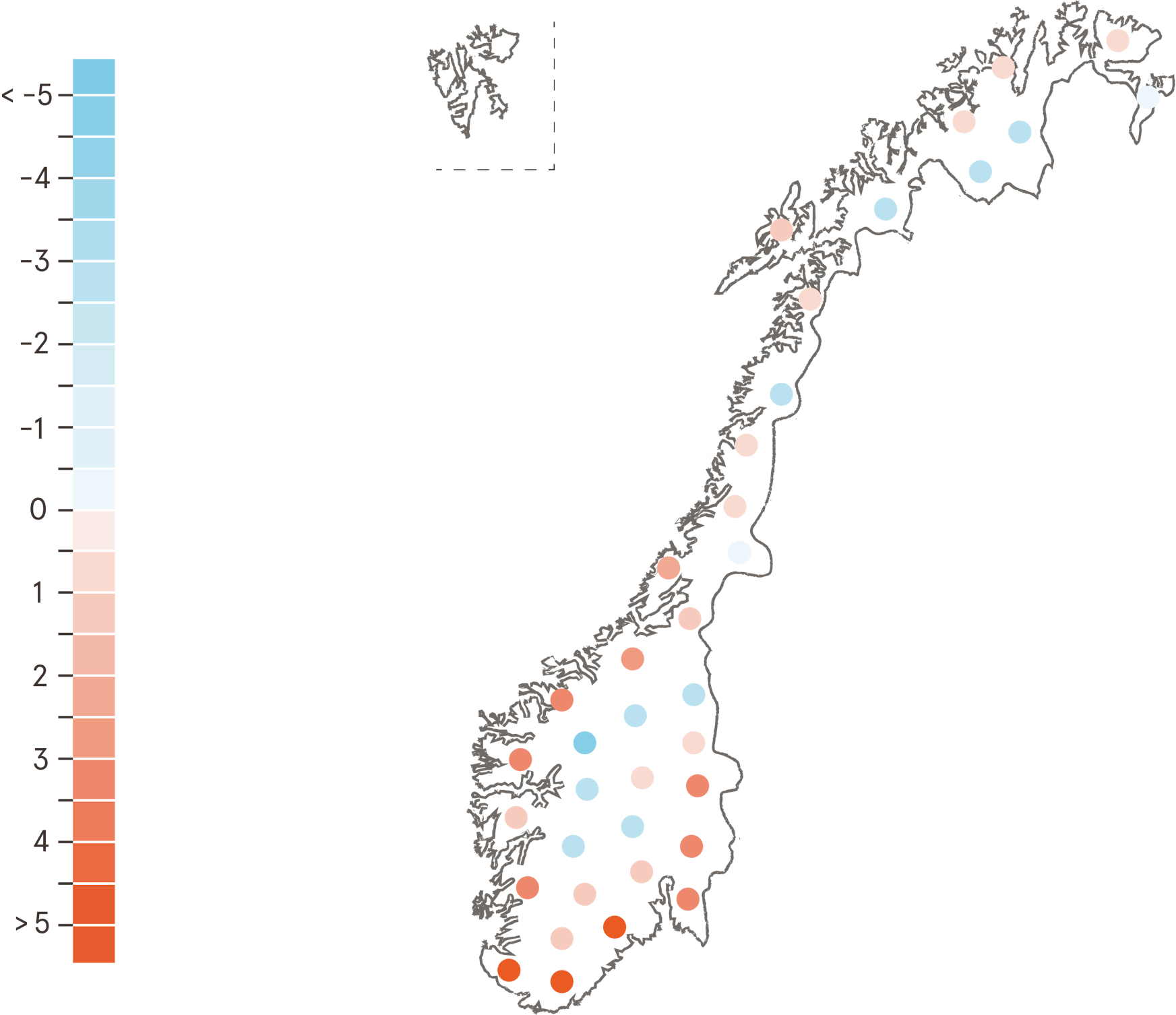

Norway has four distinct seasons with cold winters, warm summers, and a variety of temperatures. Because of the Gulf Stream, the coast experiences milder temperatures, and so does the southern part of mainland Norway, which leads to warm, yet sometimes temperamental summers. Due to its high latitude and distinct seasons, daylight also varies dramatically. Summer days are long and bright, while winters are dark with little or no sun at all. North of the Arctic Circle, from late May to late July, the sun dips but never disappears beneath the horizon, creating the natural wonder of midnight sun. Its wintery counterpart, the northern lights, or aurora borealis, can mainly be seen in the northern parts of the country.

Average Temperatures

Norway’s relatively large surface area is made up of 38 % firm ground, 37 % is forests, and 11% is inland waters and wetland with 1 % perpetual snow and glaciers. Because of the rocky terrain, only 4 % is arable land, and just 2 % of the land area is built up, with roads making up the largest share [2].

Such harsh conditions do not support large populations. Therefore, people are few and far between, with the majority of the population centred in and around major cities such as Oslo, Bergen, Trondheim, and Stavanger. As of 1 January 2021, the population counted 5,391,369 people.

Rocky struggles, finding oil and equality-based society

Historically, this rocky land has given Norwegians, who mainly lived as fishermen and farmers, little to work with. By the end of the 1800s, Norway was one of the poorest countries in Europe. That changed dramatically with the discovery of oil in the late 1960s, which led to Norway becoming one of the wealthiest countries in the world. Even so, the government has maintained a practical and restrained attitude, investing a lot of the money into an equality-based welfare system and a sovereign wealth fund for a rainy day. The government has also financed major infrastructure development, influencing tourism and the ways in which design and architecture are integrated into nature. The equality-based society has been an important reason why Norwegian design and architecture strive to be social and accessible for as many people as possible.

Facts and numbers

Protected National Parks and UNESCO World Heritage Sites

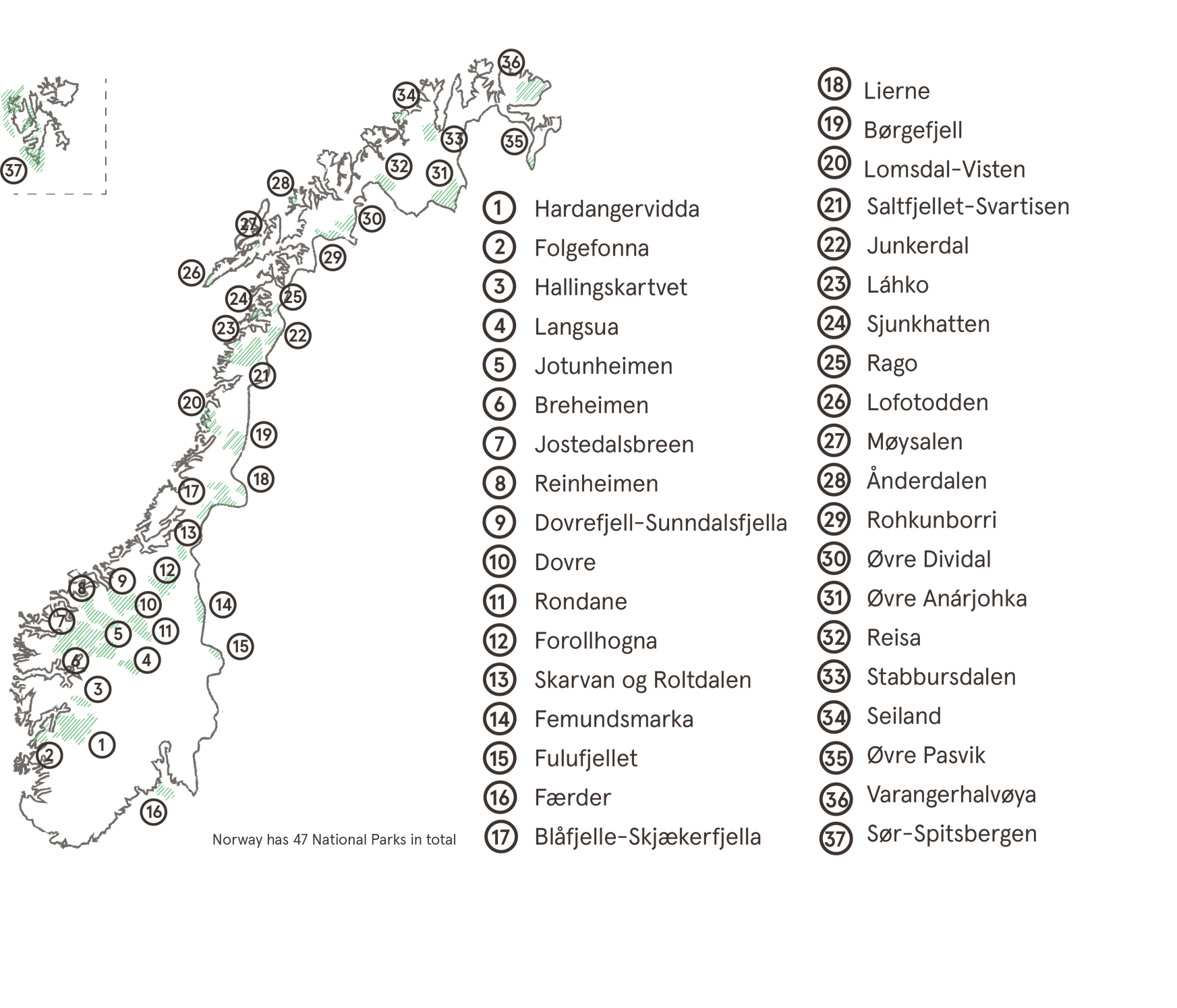

17.5 % of mainland Norway is protected through 47 national parks and 3,100 other protected areas. In addition, the island of Svalbard comprises 24 % national parks and nature reserves, while Jan Mayen has one national park. The goal is to safeguard vulnerable and threatened ecosystems and preserve areas of international, national, and regional value [3]. The protected areas are mainly mountainous terrain and small parts of the forest, coast, and sea [4].

Norway has seven cultural sites and one natural heritage site, the west coasts of Geirangerfjorden and Nærøyfjorden, on UNESCO’s World Heritage List [5].

National Parks

Legislation and Nature Protection

The government and the Storting (the Norwegian Parliament) establish the framework for Norwegian nature conservation, while the Norwegian Environment Agency, the country governors, and the governor of Svalbard carry out the conservation work pursuant to the Nature Diversity Act and the Svalbard Environmental Protection Act [6]. Other important legislation and policy to protect nature and cultural heritage include the Outdoor Recreation Act [7] and the Cultural Heritage Act [8]. Moreover, Norway is committed to a range of international conventions on biological diversity, conservation of wildlife and marine resources, climate issues, and protection of cultural and natural heritage.

The Norwegian right to roam

Outdoor recreation is an integral part of Norwegian cultural heritage. For centuries, Norwegians have been free to roam the countryside – in woodlands and meadows, on rivers and lakes, amidst coastal islets and mountain summits – no matter who owns the land. The main principles of the right to roam are legally enshrined in the Outdoor Recreation Act of 1957. However, this right to roam comes with a set of obligations. Whenever you exercise your right of access, you are obliged to do so with due care and consideration [9].

Love of nature develops the tourist sector

In Norway, people have easy access to a great variety of nature such as forests, mountains, the long and varied coastline, and parks, trails, and other green areas in towns and cities [10]. With nature so close, 90 % of Norwegians report using the vast landscape for recreation.

This love and curiosity of nature goes back a long time and has inspired many Norwegians, such as the explorer, scientist and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930). According to the Fram Museum [11], dedicated to the history of polar exploration, a widespread appreciation for nature developed in Norway in the years of Nansen's youth. As a result, outdoor life became fashionable, and those who developed physical fitness and stamina became the ideal, replacing the previous ideal of war heroes.

The Norwegian Trekking Organisation (DNT) has been important for promoting recreation in nature. It was established as early as 1868 with a mandate to “acquire means to ease and develop outdoor life here in this country". Today, DNT is Norway’s largest outdoor organisation, aiming to promote straightforward, active, versatile and environmentally friendly outdoor activities and preserve the outdoors and the cultural landscape [12]. DNT provides access to around 550 cabins around the country and maintains a network of about 22,000 km marked foot trails and 7,000 km of branch-marked ski tracks.

Unspoilt nature attracts tourism from abroad

Visitors from abroad are attracted to Norway’s unspoilt and diverse nature, with its dramatic fjords, waterfalls, glaciers, and mountainous areas for skiing or hiking, as well as the natural wonders of the midnight sun and the northern lights. Cultural and world heritage sites are also frequently visited destinations. The larger cities are popular because of cultural experiences, shopping, a growing culinary movement, modern architecture, and historical landmarks.

Tourism is an important industry and an area of priority for Norwegian authorities, as it contributes to growth, value creation and employment throughout the country. Since 2014, Norwegian tourism has experienced steady growth from abroad until Covid-19 halted all travel in 2020. In 2018, the tourism industry accounted for 4.2 % of Norway’s GDP, employed almost 170,000 people, and holiday and leisure travel counted 5.7 million travellers.

Challenges with over-tourism

Most Norwegians are proud to welcome visitors from abroad and believe that tourism leads to local growth and a range of other positive effects. However, the increasing visitor numbers can put a strain on nature, people and small communities. A report from Innovation Norway from 2019 indicates growing dissatisfaction with the rising tourism volumes, especially in small but popular destinations around the west coast fjords, the Lofoten islands and Svalbard areas, particularly during summer. Also, 23 percent of Norwegian holiday makers and 18 percent of foreign tourists felt that the places they visited were overcrowded with tourists [13].

Prior to the pandemic and the subsequent travel restrictions, pollution from increasing cruise ship tourism was becoming a significant threat to Norwegian fjords, especially the World Heritage-listed Geirangerfjord and Nærøyfjord areas. Norway has committed to ensuring that the World Heritage Sites are not exposed to harmful influences that could threaten their unique universal values. Therefore, the Norwegian government is bringing in stricter laws to reduce emissions, sewage and other waste [14].

As a positive consequence of this environmental threat, we see major innovations in greener ships and other electrical alternatives. One example is Vision of the Fjords, a hybrid-electric sightseeing boat, which fuses elegant and inclusive design with green technology. It sails in the World Heritage Nærøyfjorden and creates a unique and environmentally friendly experience for all passengers.

Regulating visitors while offering great experiences

As many protected areas are attractive tourism destinations, significant efforts have been made to develop good visitor management during recent years. The goal is to give visitors great experiences, facilitate local value creation, and create a better understanding of protection.

An essential tool in this work is visitor strategies for the protected areas [15]. The visitor strategy shows which measures – information, physical facilitation, zoning, supervision, etc. – are necessary to balance the values of nature, the visitor, and the tourism industry in a protected area, aiming to achieve the greatest possible benefit for all interests.

Norway set a national goal that by 2020, all national parks should have a visitor strategy in place to be prepared for an increasing number of visitors. For other protected areas, such strategies are created when needed [16]. In addition, visitor strategies are a requirement in order to use the official Norway National Park branding [17].

Effective visitor management [18] requires that the management of the protected area is seen in connection with the management of the surrounding areas . Therefore, a good collaboration must be established with local and regional planning authorities and tourism actors so that the visitor strategies can be coordinated and incorporated into regional and municipal short-term and long-term plans.

Redirecting visitors to less vulnerable areas

Rondane National Park is the oldest national park in Norway and contains ten peaks over 2000 metres. The mountainous area is also an important habitat for one of Europe’s last surviving wild reindeer herds. As a popular destination all year round, especially for hiking, nature is experiencing damage to the vegetation and ecosystem and erosion due to the frequent use of the area’s paths. Also, despite DNT and local tourism industries signposting official trails, unofficial paths and signs are a problem; aesthetically, for the vegetation and due to disturbance to the migration of wild reindeer. Some of the measures in Rondane’s visitor strategy [19] include removing unofficial signage, closing paths through vulnerable areas, and promoting and redirecting visitors to lesser-known and less vulnerable areas of the park.

Consistent visual communication

To ensure an overall consistent expression and communication of Norway’s National Parks, a visual identity and design manual have been created. Designed by renowned architect and design company Snøhetta, the identity is built on the concept of a portal into the finest of Norwegian nature, reminding us that it is to be both enjoyed and protected [20]. The identity defines official signage and information to visitors about the area and their responsibilities, and an official website with maps of all locations, facts, what to experience, and information about flora and fauna [21].

Observing from a safe distance

Another area with similar challenges is the nearby Dovrefjell National Park, famous for its mountain range that forms a barrier between the northern and southern parts of Norway. Dovrefjell is rich with plant and animal life, such as wild reindeer and the rare musk ox. To enjoy the scenery and the animals from a safe distance and provide shelter from the elements, the Norwegian Wild Reindeer Foundation commissioned Snøhetta to create an observation pavilion. Overlooking the mountain Snøhetta, the glass and raw steel pavilion is used for educational programmes and is open to the public.

Healing the landscape with invisible design

The area of Hjerkinn is also at the heart of what became Norway’s biggest act of restoring nature. The Landscape Healing project started in the early 2000s when the Norwegian Defence Estates Agency (NDEA) hired 3RW architects to create a national plan to rehabilitate firing ranges and training areas owned by the forces. It has since restored vast areas of land across Norway owned by the NDEA, containing polluted soil and water, unexploded ordnance, and abandoned buildings, after decades of military training activities.

Innovation Norway – tourism administration and funding

Innovation Norway is the government’s main instrument for value-creating business development throughout the country. It also acts as the national tourism administration and promotes Norway as a destination through Visit Norway.

The goal of its three-part mandate of promotion, development and competence is to contribute to a profitable development of the tourism industry within a framework that also safeguards environmental and social values. Innovation Norway offers the tourism industry counselling, financing and competence and facilitates networking. Furthermore, it facilitates the development and sale of Norwegian tourism products and collects and compiles statistics and analyses for the tourism industry.

Innovation Norway is part of the Norwegian government’s toolbox for innovation. It works closely with other public organisations that provide accompanying tools, including Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA), The Research Council of Norway, and the Norwegian Industrial Property Office.

Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA)

DOGA’s role in this work is to promote design and architecture methods to achieve innovation and create economic, social and environmental values in Norwegian businesses and the public sector.

Restarting Norwegian tourism 2021-2024

In May 2021, Innovation Norway’s new national tourism strategy was launched. For the very first time, the strategy involves a national plan that encourages co-creation and collaboration across municipalities and counties, research and academia, transport companies, cultural institutions and other public and private organisations involved in the tourism industry.

The four main goals of the strategy are to:

1. Enhance value creation and contribute to job creation throughout the country

2. Contribute to Norway becoming a low-emission society

3. Contribute to attractive local communities and satisfied citizens

4. Deliver such high customer value that willingness to pay and repurchase increases

Specifically, the strategy aims to increase Norway's export revenues by 20 billion NOK and the number of jobs by almost 43,000 by 2030, and at the same time reduce climate emissions by 50 per cent.

Designing new and sustainable experiences

Design thinking is being used more and more to develop and brand unique tourist experiences and destinations to build a richer and broader picture of Norway. This work focuses primarily on three concepts: Food and drink, culture, and nature. A vital tool developed for this work is RISS, a process and practical tool using design as a method to develop, test and communicate experiences. The tool is based on the idea that there is lots of unused raw material and local attractions with significant potential around Norway.

The sustainable development of the tourism industry takes into account social, environmental and economic aspects. The work is based on ten principles of sustainable tourism for conserving nature, culture and the environment:

1. Cultural wealth

To respect, develop and highlight the historical heritage of the community, authentic culture, traditions and character.

2. The physical and visual integrity of the landscape

To preserve and develop the landscape quality, both for cities and villages, so that the physical and visual integrity of the landscape is not degraded.

3. Biological diversity

To support the preservation of natural areas, wildlife and habitats, and minimise the devastation of these.

4. Clean environment and resource efficiency

Minimising the pollution by tourism businesses and tourists of air, water and land (including noise), as well as minimising the generation of their waste and consumption of scarce and non-renewable resources.

5. Local quality of life and social values

Preserving and enhancing the quality of life in the community, including social structures, access to resources, facilities and public goods for all, as well as avoiding any form of social degradation and exploitation.

6. Local control and commitment

Engaging and providing power to the local community and local stakeholders with regard to planning, decision-making and the development of local tourism.

7. Job quality for tourism employees

To enhance the quality of tourism jobs (direct and indirect), including wage levels and working conditions without discrimination based on gender, race, disabilities or other factors.

8. Guest satisfaction and security; Quality of experience

To provide safe, satisfying and enriching experiences for all tourists regardless of gender, race, disabilities or other factors.

9. Economic sustainability and competitive tourist destinations through local value creation

To ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of tourist destinations in a long-term perspective by maximising the value creation of tourism in the local community, including what tourists leave behind of value locally.

10. Economic sustainability and competitive tourism businesses

To ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of the tourism industry in a long-term perspective.

Certifying green destinations

As visitors become more aware and environmentally conscious, Innovation Norway is increasingly promoting green travel [22]. It rewards and promotes destinations that are committed to being greener through the Award for Sustainable Destinations, with the aim to make it easy for visitors to make a green choice [23]. The work also includes several certifications that operators can apply for to document their environmental efforts.

Making Norway an all-year-round destination

One of the biggest challenges in the tourism industry is the considerable seasonal variation. Innovation Norway’s action plan for tourism “Norway all year round” aims to spread the tourist traffic across several locations and seasons to enable year-round operation.

Other specific actions to avoid over-tourism and promote sustainable tourism are:

– Innovation Norway does not market Norway as a cruise destination

– As transport is a major dilemma of tourism and constitutes a large proportion of the CO₂

emissions from this industry, Innovation Norway encourages and supports soft mobility,

climate-friendly buildings and transport solutions.

– Innovation Norway does not finance non-sustainable activities

Tourism governance and funding

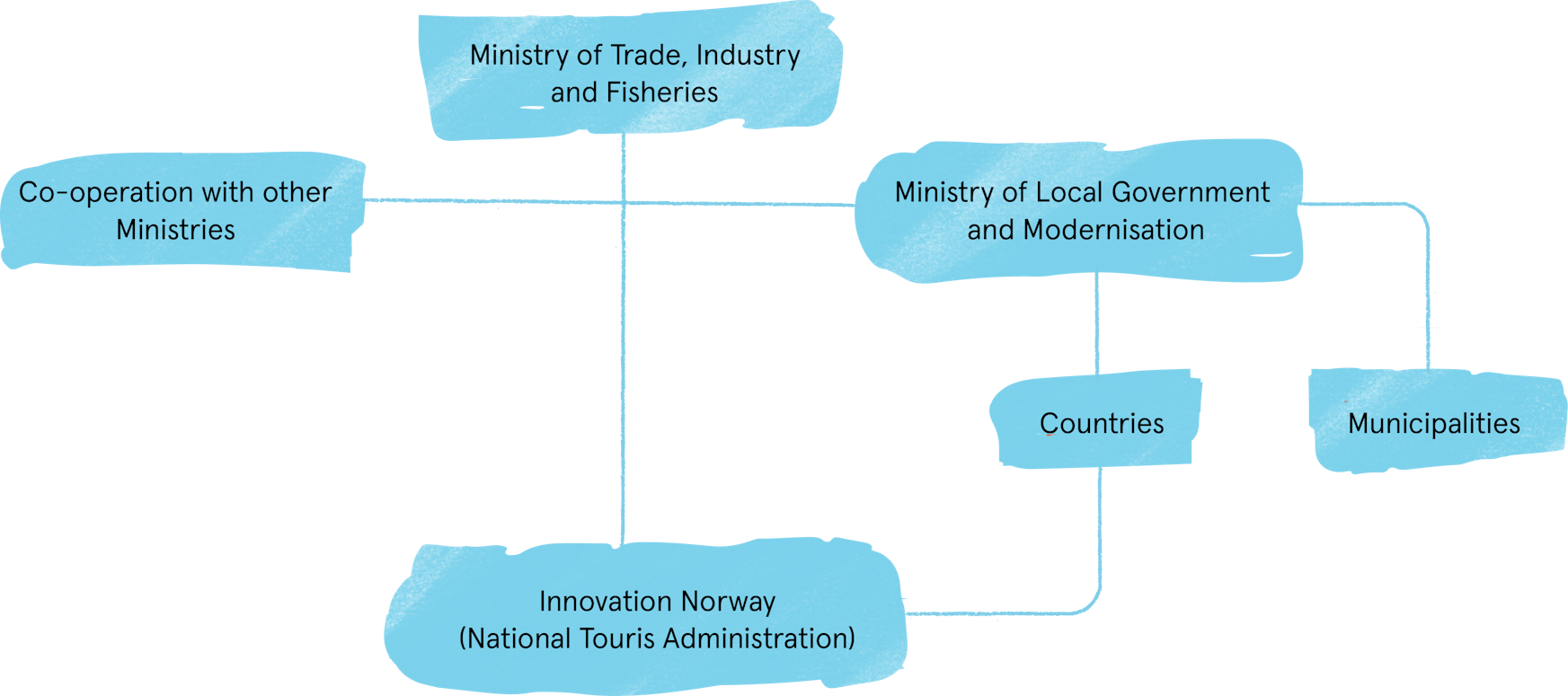

Responsibility for the development and regulation of tourism lies with the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries. The Ministry co-operates with other ministries to coordinate policies of importance to tourism. One example is the extended cooperation with the Ministry of Culture to showcase the potential for increased value creation between the cultural, creative and tourism sectors. The Ministry of Climate and Environment is another key partner, given its role in developing policies to promote a more sustainable tourism sector.

Norwegian Scenic Routes – design enriching nature

One of the biggest financial contributors to design in Norwegian nature is the Norwegian Public Roads Administration, a subordinate agency of the Norwegian Ministry of Transport responsible for the Norwegian Scenic Routes programme. The programme involves 18 road routes that run through breathtaking Norwegian landscapes, enriched with viewpoints, rest and service areas designed by innovative architects and artists. The design aims to be bold and functional. Materials and workmanship must also be of the highest quality, as the sites need to stand the test of time and harsh weather.

The project aims to make Norway an even more attractive destination, to promote local businesses and strengthen rural communities. The programme involves collaboration with seven county administrations and 57 municipalities, other public bodies, local organisations, and business communities.

In 2023, Norwegian Scenic Routes will emerge as a fully-fledged attraction with 249 attractions along just over 2,000 kilometres of road. From 2024, the routes will be operated, maintained, and developed further. According to Norwegian Scenic Routes [24], NOK 4.6 billion will be invested in the Norwegian Scenic Routes attraction from 1994 to 2029. The Ministry of Transport will contribute NOK 4 billion. Other participants will contribute the rest, mainly the county administrations and municipalities. Most of the funds from other participants are party to a joint venture to develop ten prominent attractions, notably tourism icons Trollstigen and Vøringsfossen.

Collaboration across borders

Regional and local authorities are a major influence on tourism development. They establish the conditions of key importance to tourism, with responsibility for planning and regulation in areas such as infrastructure, utilities, national parks and numerous local attractions linked to natural and cultural heritage. Some regions and municipalities have strategies for tourism, and many give financial support to their local Destination Management Organisations.

In 2020, Norway implemented a regional reform process to reduce the number of counties, with those that remain being enlarged, with renewed roles and broader responsibilities. This reform is expected to benefit the tourism industry, interacting with many sectors and stakeholders across current regional borders.

Organisational chart of tourism bodies

Sami cultural policy

The Cultural Heritage Act

Environmental governance

Design policy such as Norwegian Scenic Routes

Cultural policy for the Built Environment

Related policies

The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation has the overall responsibility for coordinating national Sami policy. The Ministry of Culture has sectoral responsibility for Sami art and culture.

Pioneering environmental governance

In 1972, Norway became the first country in the world to have a ministry at the cabinet-level with special responsibility for environmental matters. The aim of the new Norwegian Ministry of the Environment was "to work for the best possible balance between the utilization of our resources for economic growth, and the protection of natural resources for the benefit of human well-being and health."

Gro Harlem Brundtland presents the report from the UN’s World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future in 1987. The Brundtland report focused on global sustainability.

Henrik Laurvik / NTB Scanpix

Henrik Laurvik / NTB Scanpix

Governance today

National environmental governance in Norway is organised hierarchically. The Ministry of Climate and Environment is the leading government institution regarding environmental issues. Much of the work is delegated to a set of subordinated directorates:

The Norwegian Environment Agency, Directorate for Cultural Heritage, Norwegian Polar Institute and Norwegian Radiation Protection Authority. The directorates generally buy services from research institutions and consultants to cover environmental monitoring and assessments. Furthermore, much work is delegated to the County Governors, of which there are 11. The 356 local municipalities also play an essential role in the implementation of environmental policies.

Design traditions and local craftsmanship

Durable design that shelters from the harsh climate

Historically, design in nature has primarily been about providing shelter for people, animals or property from the harsh Norwegian weather. This meant that all buildings needed to be sturdy and long-lasting, using solid and durable materials. The foundation of long-lasting quality is still as valid in buildings today. The Norwegian architectural legacy includes many types of buildings, from simple shelters to the advanced stave churches and Viking ships and sturdy wooden farm buildings. This heritage is a unique source of knowledge about our past as well as craftsmanship and material use.

Gapahuk

Early travellers, timbermen and hunters often sought rest and protection from the weather in simple structures such as a lean-to shelter called Gapahuk. Originally made with whatever materials available in the forest, such as twigs and peat, it was built with an opening at the front to provide warmth from a fire and a pitched roof with two or three walls. It later evolved into a log structure, using a technique where horizontal logs are interlocked at the corners by notching. This log technique became the most dominant way of building wooden houses in Norway from the Viking Age until the middle of the 19th century.

Today, we see the influence of the Gapahuk and the log technique in many modern designs. For example, Norwegian architects Biotope have made a modern version of the gapahuk, inspired by the simple Nordic outdoor life. Biotope designs what they call small rooms for large nature experiences - modern yet simple buildings with clean lines, made to withstand weather and wind and provide a space to get close to nature [20][1].[1]

Biotope Gapahuk

Biotope Gapahuk

Sámi design leave no trace

The indigenous Sámi people sought shelter in structures called goahti, or gamme in Norwegian. Built by logs clad with peat, the shelters were used in the areas where the Sámi people lived, from Hedmark in southeastern Norway to Finnmark in the north. The gamme could be used as a barn or a dwelling and was sometimes shared by people and animals.

Lavvo is another traditional Sámi tent that has been used for over 2000 years. It is easy to move around and is therefore well suited to the Sami's traditional nomadic life, leaving no trace in nature. Traditionally, the lavvo is made from sticks in the shape of a cone with reindeer skin over it. It has a fireplace in the middle with an opening that lets the smoke out. The Lavvo typically has a separate dining area, woodshed and sleeping accommodation.

The Sami Settlement at Norsk Folkemuseum

Anne-Lise Reinsfelt / Norsk Folkemuseum

Anne-Lise Reinsfelt / Norsk Folkemuseum

Today, lavvo has evolved from being a place where the Sámi people resided to a popular and sturdy shelter used in outdoor recreation all over the country. The Kautokeino-based company Venor, the world’s oldest manufacturer of lavvo, has developed new versions where the wooden poles have been replaced with aluminium to make the lavvo easier to carry. Still using traditional craftsmanship, the tents are handmade with durable materials.

The influence of traditional Sámi design can also be seen in contemporary architecture, such as the Sámi parliament building in Karasjok. Designed by architects Stein Halvorsen and Christian Sundby, it reflects Sami traditions with a peaked structure of the Plenary Assembly Hall that resembles the Sámi tents.

Sámi parliament building in Karasjok

Jaro Hollan

Jaro Hollan

More from here

https://lokalhistoriewiki.no/index.php/Samisk_byggjeskikk

https://arkitektur-n.no/temaer/samisk

https://www.arkitektur-n.no/artikler/samtidig-samisk-arkitektur

More on developing Sami tourist experiences

Norwegian wood

Endowed with an abundance of quality natural materials such as wood, Norway has a proud and longstanding tradition of craftsmanship. This can, for example, be seen in the elegant and sturdy construction of Norway’s stave churches and Viking longships, which represents Norway’s most important architectural heritage.

Steve Churches – Norway’s contribution to world architecture

Wooden stave churches tell the story of craftsmanship found in Norway with respect to structure, materials, decoration, and interior. As many as 2,000 stave churches were built from the first half of the twelfth century until the Black Death devastated Norway in 1349. At the time, more than a thousand villages had a stave church, but only 28 of them survive today. The oldest and most decorated, the Urnes Stave Church, built around 1130 AD, was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1979.

The churches were built using an advanced stave construction without glue and nails. The name of the stave churches comes from the buildings' advanced post and beam construction, a type of timber framing where the load-bearing ore pine posts are called stafr in Old Norse. For a detailed description of how the stave churches were constructed, see the extensive research by architect, PhD. Jørgen H. Jensenius.

The stave churches and wooden construction have influenced many contemporary builds. One example is the Norwegian Armed Forces’ military camp at Rena, finished in 1997 and designed by Norwegian architects LPO Arkitekter. Camp Rena is characterized by extensive use of wood using modern interpretations of old building traditions. For example, some of the walls are cladded with chips from ore pine, a method traditionally known from the Norwegian stave churches.

Urnes stave church wooden cladding.

Joe Becker

Joe Becker

Rena Leir

Photo: LPO Arkitekter

Photo: LPO Arkitekter

Preserving the stave churches for future generations

According to the stave church society, Stavekyrkjeeigarforum, maintaining the stave churches is very demanding. In the 1990s, many of the churches were in a state of disrepair because of a lack of maintenance. Consequently, the Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage established a national stave church programme in 2001. The objective was to repair the stave churches, the decor and church art, and supplement documentation to provide a basis for research and the reconstruction of missing parts. This ambitious programme was carried out between 2001 and 2015 and has cost the Norwegian state a total of around NOK 130 million.

In addition to preserving valuable heritage, many artisans who took part in the programme have acquired new knowledge about traditional craftsmanship and future maintenance of the stave churches.

Vernacular design traditions

During the Middle Ages, Norway’s geography dictated a widely spread population and economy, which resulted in a strong farming and fishing culture. Unlike the rest of Europe, Norway never adopted feudalism. Combined with the availability of wood, this developed distinctive traditions in vernacular architecture using lafteverk (Norwegian for log construction), and fewer examples of the architecture styles more frequently seen in Europe. Vernacular traditions have therefore been important influences on Norwegian architecture, both farm buildings, homes and cabins.

The technique of “Lafting” came to Norway via Sweden in the Viking Age and was the dominant construction method in Norway until the end of the 19th century. It consists of logs that are laid horizontally and alternately stacked on top of each and locked together in the corners. A good lafteverk wall seals against weather and wind and is heat-insulating. It is therefore well suited for both residential houses and farm buildings.

The wooden traditions can also be found in new structures, such as the pedestrian bridge at Kjærra, which spans across the Numedalslågen river. The timber bridge designed by architect Arne Eggen Arkitekter AS was part of a municipal effort to improve access to the public riverbanks.

Social and resilient design for all

In the 20th century, Norwegian architecture has been characterized by social policy on one hand and innovation on the other. As Norway’s society is based on equality and trust and the Norwegian right to roam, nature is largely available to everyone, regardless of status or level of income. Combined with the massive health benefits of being in nature, this is probably why the Norwegian government for years has been investing in and using design and architecture to make nature more attractive and accessible for everyone – as seen in initiatives like Norwegian Scenic Routes and Landscape Healing.

Some ground-breaking private companies are paving the way too. Norwegian manufacturer Vestre has made durable outdoor furniture for over 70 years and is pioneering in sustainable development and social responsibility. Due for completion at the end of 2021, Vestre is currently building The Plus, the world’s most environmentally friendly furniture factory in the middle of the forest in Magnor. The factory is designed by Bjarke Ingels Group and aims to be a global showcase for sustainability and manufacturing with a visitor centre and park that will also help develop Magnor as an attractive destination for visitors from all over the world.

Current designs and future visions

Designing attraction: a quest for balance

Nature is never far away in Norway and continues to be an essential feature of many of our architectural and design projects. Our buildings are subjected to powerful natural forces, prolonged periods of ice and snow, along with rain, sun and wind, creating the need for high-quality, durable design and construction.

Wood is still a widely available and well-known building material. Also, materials such as stone, steel or glass are used to reflect the surrounding landscape in modern buildings. Some are even designed to appear at one with nature, like Oslo’s National Opera and Ballet, which seems to float like an iceberg on the fjord. At the other end of the scale, there is the Juvet Landscape Hotel, where tiny cabins made from wood, steel and glass are tucked away to become one with the forest.

Social and inclusive design

The Norwegian model of an equitable society has undoubtedly influenced modern architecture and design, encouraging inclusive and sustainable buildings and environments, both in terms of climate and social aspects. [1]

The Norwegian government has a vision for Norway to be universally designed by 2025, which will provide better and more equal surroundings for people with disabilities and everyone else. Universal design also contributes to social and economic sustainability. Therefore, it is part of the national sustainability strategy and the new Planning and Building Act to help make society accessible to all and avoid discrimination.

Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA) administers a programme called Innovation for All, funded by the government, intended to contribute to a more inclusive society in which products, services and public spaces are designed to focus on human diversity, inclusion and equal opportunity for all. One of the main activities is the Innovation Award for Universal Design, which honours businesses, designers and architects who have innovatively designed products, services and environments that contribute to creating a more inclusive society.

Awarded for its equality-based design recently is the Hamaren Activity Park, an easily accessible park in the county of Telemark, which promotes physical activity within nature to improve health and well-being. Commissioned by the Municipality of Fyresdal, the park quickly became a social gathering point for the entire population.

Close to nature and the unique experience

Because of the pandemic, it is estimated that the Norwegian tourism industry lost around 60 billion NOK in 2020, and it still faces a very uncertain future. As a reaction, Innovation Norway has launched an ambitious three-year strategy to restart the industry after the pandemic. But difficult times also breed creativity, new opportunities and a change in trends. Recently, a growing trend has seen small and unique places popping up in new breathtaking locations that offer an overnight stay as close as possible to untouched nature.

One of the structures used for this kind of close-to-nature tourism is the Birdbox, designed by Torstein Bergheim Aa. It is a prefabricated room that can be placed in unique places in nature and provides modern comfort and shelter. Yet, it is designed with high quality in material use and design to ensure minimal intervention in nature.

Minimal design, minimal footprint

If visitors are to experience this close contact with raw, untouched nature, the footprint in nature needs to be minimal. When the local tourist association in the windswept west coast town of Haugesund commissioned Holon Arkitekter to design a series of small cabins, the brief was not to leave any permanent trace in the landscape.

The result is Flokehyttene which opened in 2020, a series of five cabins that claw their way into the rock crevices as if waiting for the next wave. Inside, you can sit in sheltered and comfortable surroundings and experience the open sea through large panoramic windows. The only thing holding the cabins to the rocks are three-meter-long steel poles, and the boreholes for these poles are the only traces the cabins will leave the day they are removed.

Holon

Holon

When does design go too far?

When installing structures into nature, it raises the question of what is most important, design or nature? Getting the balance right can lead to a successful marriage where design enhances nature and nature enhances design. The work chosen for the National Scenic Route, for example, is required to show great consideration for the location. Materials and workmanship must have the qualities to ensure the durability of the tourist route attraction, that they stand the passing of time and require low operation and maintenance costs.

Vøringsfossen by the Hardanger National Park is perhaps the best-known waterfall and one of Norway’s most visited tourist attractions. But the area showed signs of long-term wear and tear, and several viewpoints were not adequately safe, which resulted in several tragic accidents. The architect Carl-Viggo Hølmebakk was commissioned by the National Scenic Route to create an entirely new experience of the areas through a safe tourist trail along the edge of the cliff, service facilities and a spectacular bridge across the gorge.

The new step bridge was finished in August 2020. It is expected to attract more tourists to the area and generate more value for local businesses and the community. However, the bridge has also met criticism, and local politicians have called it an ‘abuse of nature’, arguing that the very unspoilt nature that people come to see is being ruined. Still, in 2020, the prestigious American The Architizer Award named Vøringsfossen the winner in several classes.

How much design is too much?

Undisturbed Norwegian nature has drawn visitors from far and near for ages. The Norwegian tourist industry has been growing fast during the last decade, but as a paradox, the increasing number of tourists and the way they are being transported here by planes, cars and ferries is becoming a threat to the very fragile nature they are coming to see. Although much good work has been done to develop greener tourism, it wasn’t until Covid-19 halted all travel in 2020 that the industry had a proper opportunity to pause, re-think and make plans to restart the tourist industry after the pandemic in a more sustainable way. So while design and architecture can enrich our nature experiences and make nature more accessible, moving forward, we must always ask what gets the main focus. Is it design, or is it nature? And how much design is too much? Norway’s undisturbed nature must always remain its main attraction.

References

[1] Statistics Norway: Facts about Norway https://www.ssb.no/en/natur-og-miljo/statistikker/arealdekke

[2] Statistics Norway: Proportion of land areas https://www.ssb.no/en/natur-og-miljo/artikler-og-publikasjoner/forest-mountain-and-moorland-dominate

[3] Norway’s National Parks: https://www.norgesnasjonalparker.no/verneomrader/

[1] Conservation Areas: https://miljostatus.miljodirektoratet.no/tema/naturomrader-pa-land/vernet-natur/

[1] UNESCO World Heritage List: https://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/no

[1] Svalbard Environmental Act: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/svalbard-environmental-protection-act/id173945/

[1] Outdoor Recreation Act: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/outdoor-recreation-act/id172932/

[1] Cultural Heritage Act: https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/cultural-heritage-act/id173106/

[1] Norwegian Environment Agency: Right to roam https://www.environmentagency.no/areas-of-activity/right-to-roam/

[1] Environment Norway: Outdoor recreation https://www.environment.no/topics/outdoor-recreation/

[1] Explorer Fridtjof Nansen https://frammuseum.no/polar-history/explorers/fridtjof-nansen-1861-1930/

[1] The Norwegian Trekking Organisation https://english.dnt.no/about/

[1] Innovation Norway: Key Figures for Norwegian Travel and Tourism 2019

https://business.visitnorway.com/no/markedsdata/nokkeltall/

[1] Visitor management in protected areas https://www.miljodirektoratet.no/ansvarsomrader/vernet-natur/myndigheter/besoksforvaltning-i-norske-verneomrader/

[1] Challenges and measures about increased tourism to protected areas https://miljostatus.miljodirektoratet.no/tema/naturomrader-pa-land/vernet-natur/

[1] Design manual for National Parks https://designmanual.norgesnasjonalparker.no

[1] Guidelines for visitor management https://www.miljodirektoratet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/M415/M415.pdf

[1] Visitor strategy Rondane National Park https://designmanual.norgesnasjonalparker.no/uploads/documents/Besøksstrategi-Rondane-nasjonalpark_nov2015.pdf

[1] Official website for Norway’s national parks https://www.norgesnasjonalparker.no/en/

[1] Visit Norway: Green Travel https://www.visitnorway.com/plan-your-trip/green-travel/?lang=uk

[1] Visit Norway: Sustainable destinations https://www.visitnorway.com/plan-your-trip/green-travel/sustainable-destinations/?lang=uk

[1] Norwegian architecture today: https://doga.no/en/activities/design-and-architecture-in-norway/architecture/architecture-in-norway/

[1] “No er brua over Noregs best besøkte naturattraksjon på plass”, NRK,her July 2nd 2020

Author information

Knut Bang, Senior Adviser Design, Design and Architecture Norway (DOGA)

kb@doga.no