By Svend Bilo Høegh Stigsen

The tourism industry in Greenland is not focused on mass tourism but rather on adventure tourism, which poses interesting design challenges. How do we design for the few, in a sustainable way, in Greenland’s fragile nature?

Tourists from all over the world want to experience the raw and untouched nature of the Arctic. As a result, Greenland has started preparing for rapid and significant growth in tourism in the coming years, partly by upgrading the flight infrastructure with the addition of two new airports. Currently relying on two former US military airports for international flights, Kangerlussuaq and Narsarsuaq, Greenland is constructing two new modern airports: one in Ilulissat in the north of Greenland and another in Nuuk, the capital city. A third regional airport is being planned in Qaqortoq in the south of Greenland.

One thing is to get tourists safe and sound to Greenland, but another is to prepare an entire industry. To accommodate the tourism growth, there is a need to further develop infrastructure and services in the sector, such as accommodation, restaurants, and guided tours introducing visitors to the magnificent scenery, culture, and history. All of this must be developed in close collaboration with the local communities in Greenland, with the utmost respect for the country’s cultural and natural heritage.

Interactive Map

General characteristics of Greenlandic nature and tourism

A land of contrast

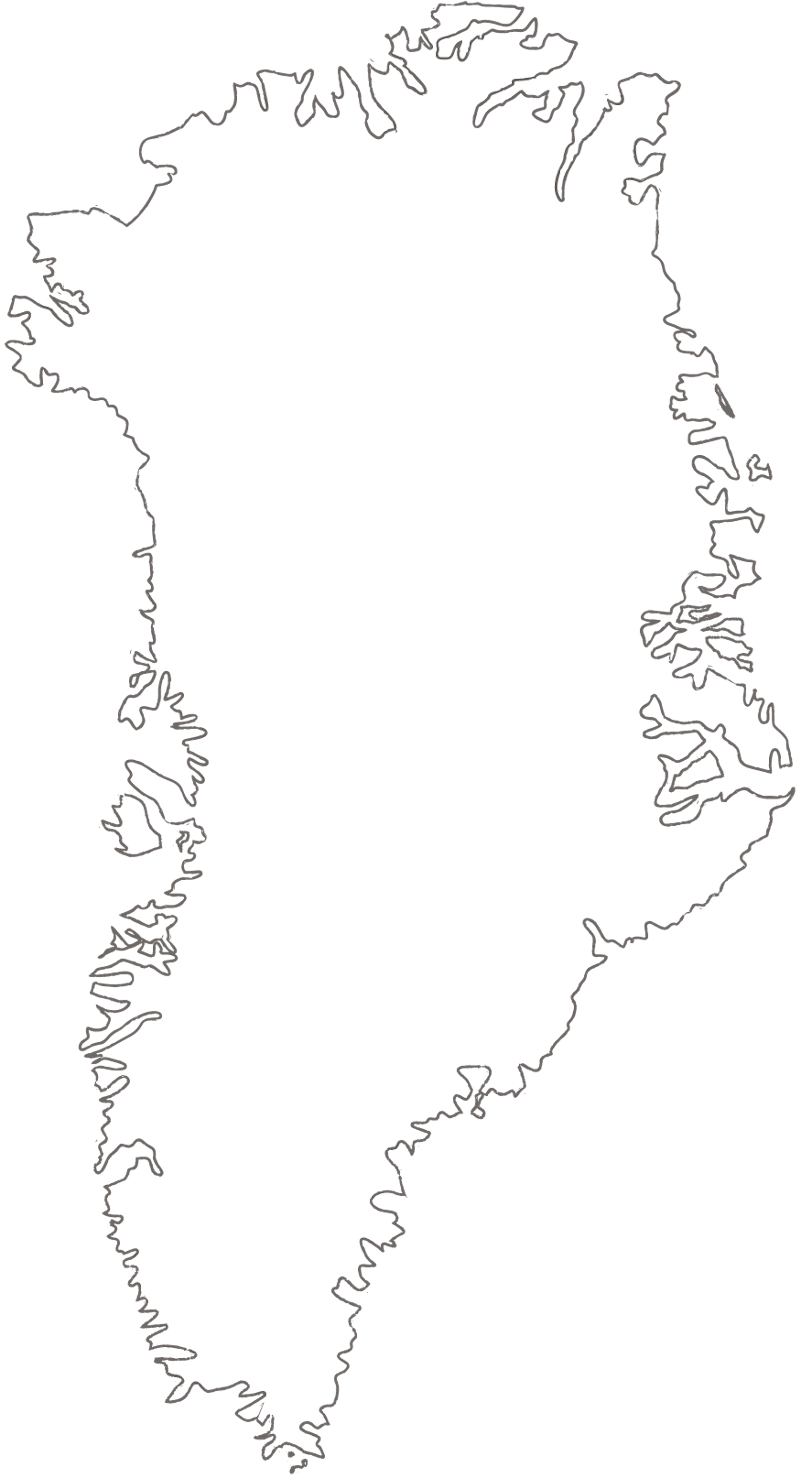

Greenland is the world’s largest island, with 2,166,086 km2 of land. The Greenland ice sheet is the largest in the northern hemisphere, covering around 80% of the country. Greenland’s coastline is an impressive 44,000km. There are 18 cities in Greenland and 58 hamlets, all located along the coast. The total population is approximately 56,500 people. Around 19,000 people live in Nuuk, the capital, whereas some of the smallest hamlets, such as Isertoq near Tasiilaq on the east coast, have less than 60 inhabitants. Greenland is truly a land of contrast.

Facts and numbers

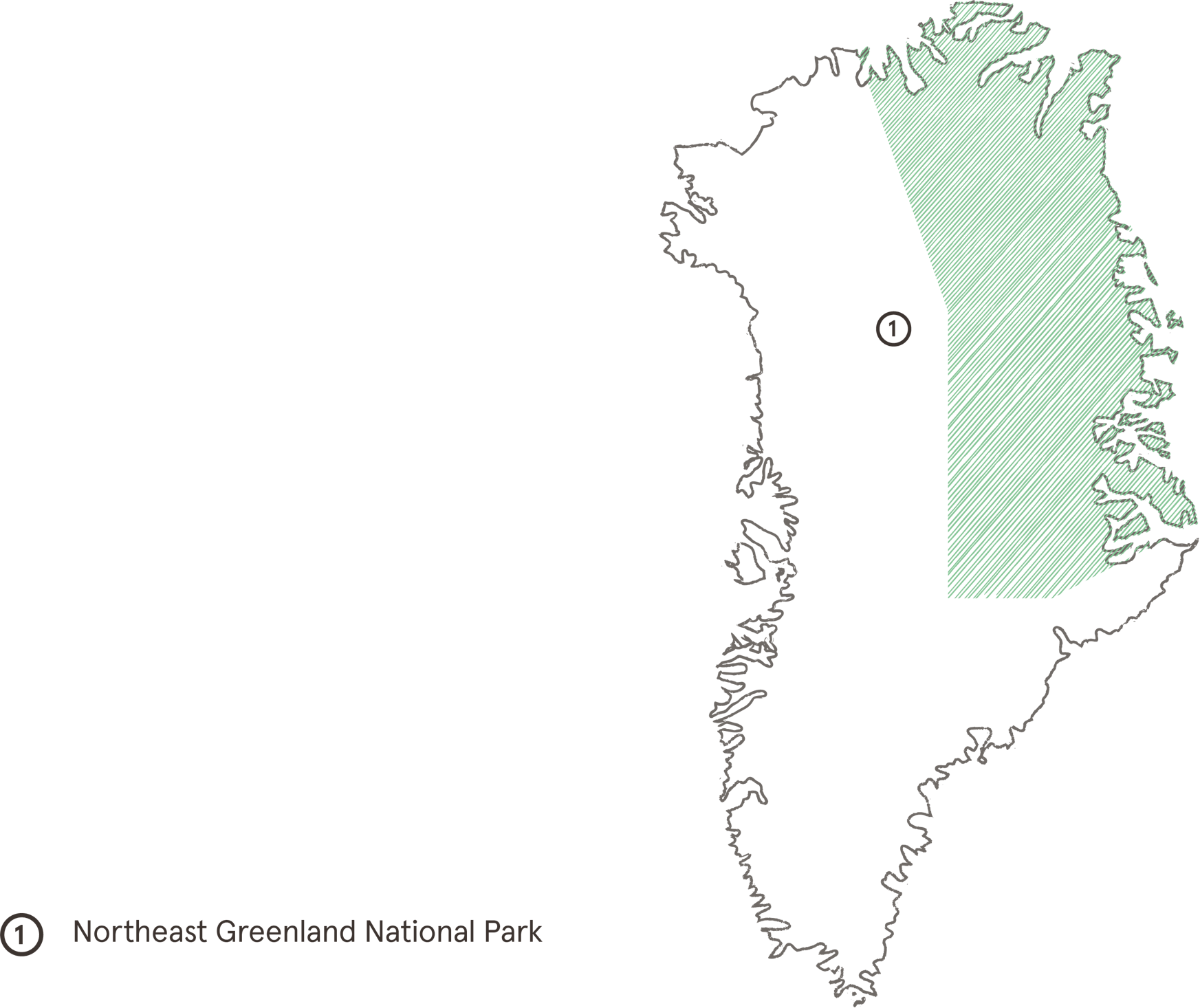

The Greenland National Park

Greenland is home to the world’s largest national park, covering an area of 972,000 m2. It includes the entire northeastern part of Greenland, north of Ittoqqortoormiit, including the world’s northernmost land area. Its coastline extends over 18,000 km.

However, the Northeast Greenland National Park is somewhat different from most national parks in other countries. The only people who have access to the area on a regular basis are local hunters and fishermen from Ittoqqortoormiit, and there are no organised tours for visitors and tourists. Apart from the personnel at meteorological and monitoring stations and the Danish Sirius Patrol, around 40 people in total, no one lives in the national park.

National parks

Infrastructure

Infrastructure in the Arctic is a challenge, and Greenland is no exception. The distances are vast, nature is rough, and the weather can be extreme.

There are no roads between the inhabited places, so all traffic is by helicopter, aeroplane, boat or skidoos, and dog sleighs during winter. All the cities and hamlets therefore operate like small, isolated islands.

Travelling to and within Greenland can therefore be a challenge. The international airports in Greenland are old American Air Force bases, placed in isolated locations for strategic reasons. They are not placed near any of the major settlements, meaning that most travellers must also fly domestically to reach their destination.

But things are changing. The Greenlandic Government is planning three new airports in the regional cities of Ilulissat in the north, Nuuk in the middle, and Qaqortoq in the south. The airport in Nuuk is set to open in 2024, the one in Ilulissat the year after, while construction of the regional airport in Qaqortoq commences in summer 2022. These new airports will change the way people travel to Greenland and transform domestic travel in the country.

In the coming years, the cities will have to upgrade local infrastructure, build accommodation, and familiarise people with the tourist industry. This preparation phase should be seen as an opportunity to develop design strategies with a local touch. It provides an opportunity to offer future guests a unique Greenlandic design experience; of infrastructure, architecture and carefully executed design solutions in nature, such as boardwalks, information signs, and simple harbour solutions in the fjords of Greenland.

Road construction in Sisimiut

With 5,700 inhabitants, Sisimiut is the second-largest city in Greenland. Located only 200 km from the international airport in Kangerlussuaq, the city is not part of the current airport expansion plans. To improve connectivity, the municipality of Qeqqata has therefore initiated an ambitious road project, the Arctic Circle Road, connecting Sisimiut and Kangerlussuaq.

Arctic Circle Road

As the infrastructure is changing with new international airports in Ilulissat and Nuuk, Greenland’s second-largest city, Sisimiut (Municipality of Qeqqata), is taking matters into its own hands. The municipality has started the construction of a road connecting Sisimiut with Kangerlussuaq and Kangerlussuaq Airport.

Kangerlussuaq airport is a vital infrastructure hub in Greenland. This is where Air Greenland connects the country with the outside world – that is, until the new airports open in Ilulissat and Nuuk.

A road connection between Kangerlussuaq and Sisimiut has been discussed since the early 1960s and is now finally taking shape. The project’s first step is to create an ATV track connecting the two towns, which will later be upgraded to a dirt road. Promoting tourism and creating new experiences along the new route is an important priority, including in the Aasivissuit-Nipissat area, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2018.

Sisimiut is known for its spectacular nature. It offers off-piste skiing and snowmobiling and hosts the famous 160-kilometre cross-country race, “The Arctic Circle Race”. During summer, the area provides sublime trekking, ATV experiences and fishing, and visitors can explore the unique cultural landscape of the UNESCO World Heritage Site: Inuit hunting grounds between ice and sea.

Arctic Circle Road is a game-changer for tourism for three main reasons:

1. It provides low-cost, flexible, and independent transport between the two cities.

2. It provides access to a massive land area that was previously out of reach.

3. It secures the basis for hotel investments in Kangerlussuaq, which has had difficulties attracting private investors since the closure of the US military base.

This ambitious project is an opportunity to create new Greenlandic designs for roads, shelters, viewpoints, hotels etc. For this to happen, the project should start with a design strategy, which could later form the basis for more detailed guidelines and design manuals.

UNESCO World Heritage Sites

There are three UNESCO World Heritage sites in Greenland:

- Kujataa – Norse and Inuit Farming at the edge of the ice cap

- Aasivissuit-Nipisat – Inuit hunting grounds between ice and sea

- Ilulissat Kangia – the Ilulissat icefjord

The Ilulissat icefjord was the first site in Greenland to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2004. The National Museum of Greenland and the municipalities where the sites are located are responsible for managing the UNESCO World Heritage Sites. All development projects within or close to a UNESCO-listed area must be assessed and approved by the National Museum and the municipality at hand, making sure that the project complies with the protection of the cultural heritage site.

The Ilulissat icefjord. The Ilulissat glacier is the fastest moving in the world, and the area is known for its colossal icebergs.

In 2018, the “Aasivissuit – Nipisat” was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. The area covers a traditional Inuit hunting ground, from the icecap near the city of Kangerlussuaq to the coastal town of Sisimiut. The history of this stretch of landscape goes back more than 4000 years.

Kujataa, Norse and Inuit Farming. This area shows the Norse and Inuit farming culture. The old ruins and structures go back more than 1000 years.

Laws and executive orders to protect and control the future development

The Greenlandic Government has approved several cultural heritage protection laws and executive orders to promote and protect the future of these critical sites. These include the Heritage Protection Act on Cultural Heritage Protection and Conservation from 2010, an Executive Order on Cultural Heritage Protection (2016), the Museum Act (2015), and the Planning Act (2010).

The Heritage Protection Act protects ancient monuments, historic buildings, and historical areas. Laws addressing nature and landscape protection include the Nature Protection Act (2003) and the Acts on Preservation of Natural Amenities, Environmental Protection and Catchment and Hunting.

All physical changes to the UNESCO World Heritage Sites, like paths, roads, structures, and buildings must undergo a thorough approval process with the National Museum and the municipality in which the site is located. Furthermore, all mining activities are subject to strict legal requirements, and any disturbance or demolition of the sites is punishable by law.

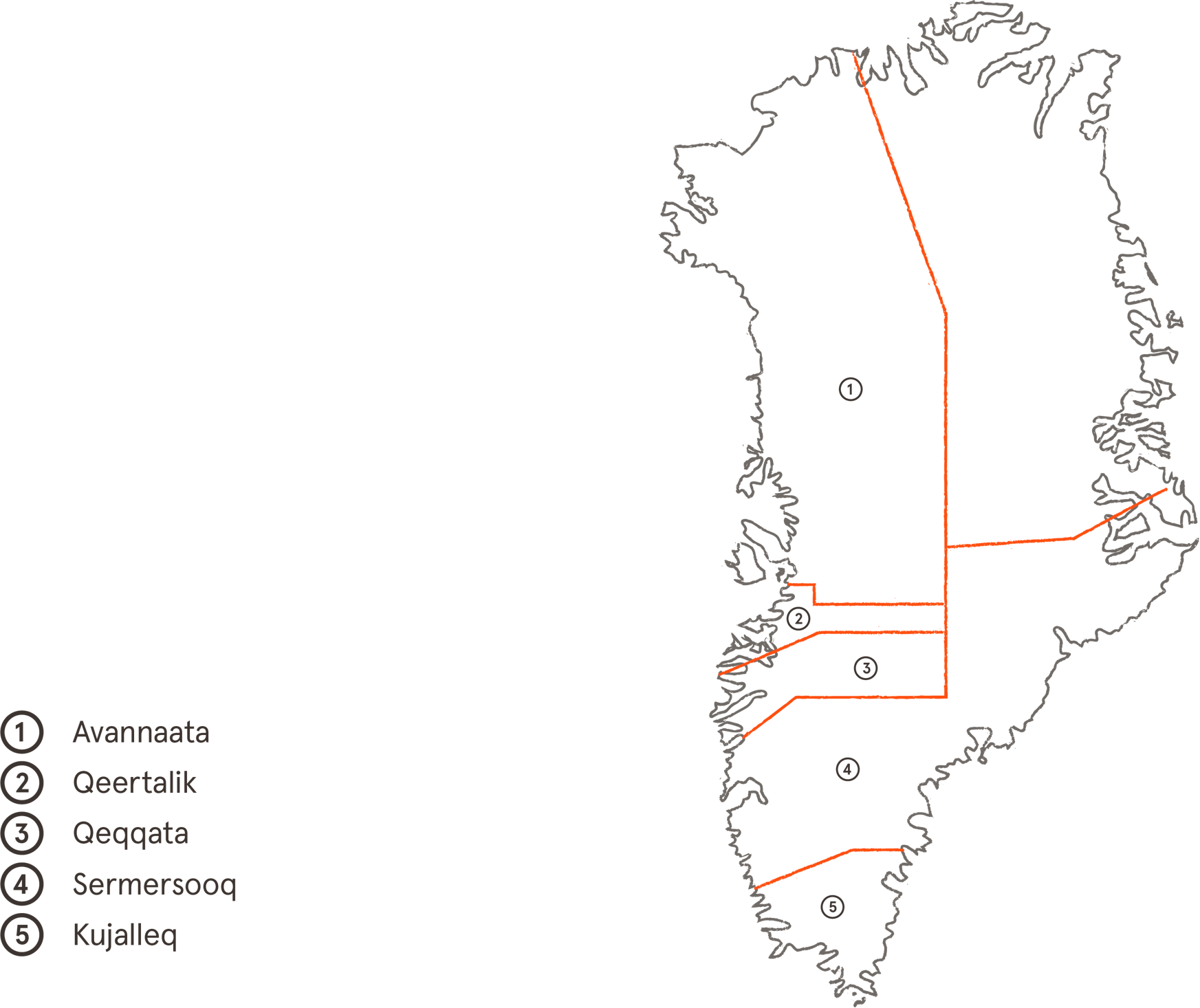

Municipalities

The Land belongs to us all

The planning law in Greenland is unique, as there is no private ownership of land. Someone building a house will not own the building plot on which the house is built but is merely granted the right to build there. The house itself, however, can be privately owned.

When the municipalities in Greenland plan for new housing areas, they determine what type of public services and buildings are required, such as schools, kindergartens, and public housing. They can also plan for private functions, such as privately owned houses, buildings, and shops. People who wish to build a house must wait for the municipality to advertise available building plots, and only those who meet specific requirements can apply. If there is more than one applicant, a lot is drawn to determine who gets the building plot.

There are two levels of planning in Greenland:

- Overall physical and regional planning is the responsibility of the Greenland Home Rule Government

- Municipal and city planning is a municipal responsibility

Greenland comprises five municipalities: Avannaata, Kujalleq, Qeqertalik, Qeqqata, and Sermersooq. In addition, there are city boundaries and hamlet boundaries, while the remaining land is referred to as “the open land”, which is also a municipal responsibility.

Tourism in Greenland

Greenland has always been an attractive destination for explorers. Greenland expeditions started in the late 1800s as polar expeditions aiming to map various areas and study their geology, wildlife, fauna, climatic conditions, or traces of human presence. Today, Greenland expeditions are carried out mainly for the sake of adventure.

Knud Rasmussen (1879-1933) is arguably the most famous Polar explorer. Born in Ilulissat and the son of a Danish missionary, Knud Rasmussen did several expeditions in Greenland. The best known is the fifth Thule expedition in 1921–1924, which visited all the existing northern Inuit tribes. 2021 is the 100th anniversary of the 18,000 km polar expedition, covering Greenland, Canada, Alaska, and Siberia.

Tourism in numbers

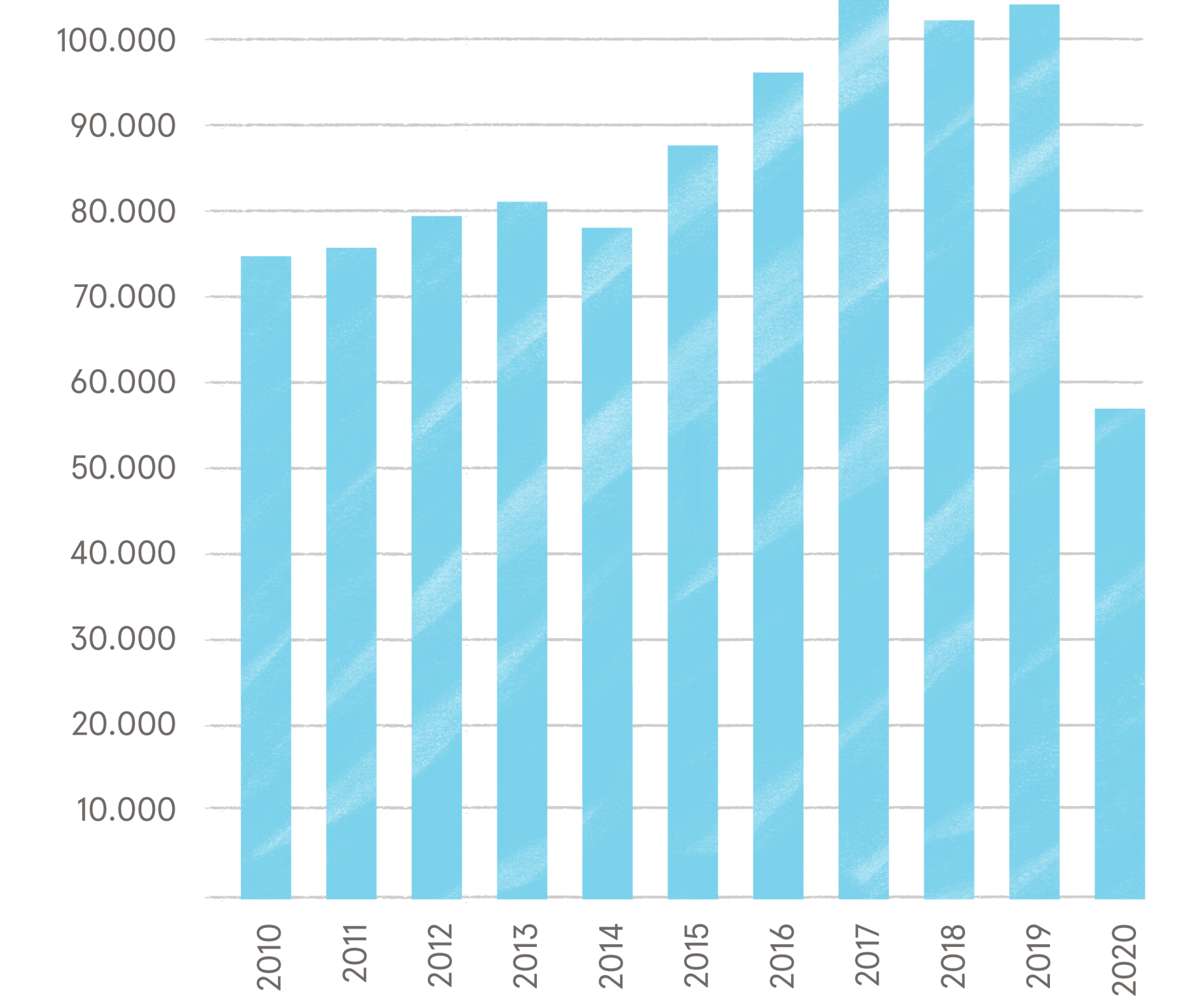

Tourism is the second biggest export in Greenland after the fishing industry. Before the Covid-pandemic hit in 2020, tourism was a prosperous business, and it will be so again.

Between 2015 and 2019, the number of international tourists in Greenland increased by 36.3%. Foreign overnight stays increased by 34% in the period, international flight passengers by 12%, and cruise line passengers by 86.2%

Development of Tourism

The National Tourism Strategy

The National Tourism Strategy 2021–2023 is published by the Department of Commerce on behalf of the Greenland Home Rule Government. The overall objective of the strategy is to ensure that Greenland will be ready for the growth in tourism when the new airports open by the end of 2023. The key focus is to ensure that the new and existing airports create the best possible framework for the Greenland tourism sector.

The strategy has three focus areas:

Firstly, ensuring sufficient capacity to receive tourists (hotels, restaurants, tours etc.).

Second, ensuring a varied offering of unique tours and experiences. And thirdly, education and knowledge-building in tourism. One could argue that these three focus areas may not be sufficient. Alongside the commercial development of tourism in Greenland, a discussion must take place about how to design future accommodation, paths and tracks in nature, signage, and so forth. What is the urban Greenland we want to welcome the world with? How do we present the untouched nature of Greenland? These are some of the questions that must be addressed in the coming years.

Visit Greenland

Visit Greenland is an independent tourism agency, established and financed by the Greenland Home Rule Government.

Visit Greenland’s strategy for 2021-2024 defines four must-wins towards 2024

1. Increased demand from adventure tourists

2. All-year-round tourism in all of Greenland

3. Knowledge sharing and competence upgrade

4. Promoting favourable framework conditions

All-inclusive tourism and adventure tourism

The all-inclusive concept includes all the essentials in the booking price. Besides accommodation, you can expect food, drinks, activities, and entertainment to be included, without having to pay extra.

Adventure tourism is defined as people exploring remote areas outside their comfort zone. This type of tourism is on the rise all over the world, and Greenland is no exception. As a result, adventure tourists are an increasingly important target group for tourism operators in Greenland.

Design Traditions

Before Greenland was colonised, Greenland was a nation of self-builders who developed their building techniques to survive in the harsh climate.

Throughout Greenland’s different development stages, the architecture has changed from primitive tent structures using driftwood, sealskin, and other available materials to more permanent turf houses and houses built from rocks. These houses were built for one or more families. The permanent structures indicated a change in the nomadic Inuit lifestyle, and settlements started to emerge.

Greenlandic/Nordic architecture

In 1952, the first housing benefit scheme was launched in Greenland, making it possible to get a loan to cover the cost of building materials. In most cases, however, people still had to build the houses themselves as skilled carpenters were hard to find outside the bigger cities and settlements. Through the scheme, the Ministry of Greenland made it more attractive to build in the bigger towns and cities, close to the main institutions. The housing benefit scheme evolved into the characteristic Greenlandic type houses, which can be seen along the coast all over Greenland.

All the houses were designed by the Greenlandic Commission’s Board of Architecture’s Office.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Greenland was influenced by modernism like the rest of the world. As a result, larger housing complexes became more common, especially in the larger cities.

In the 1980s and 1990s, 2-3 story wooden buildings became popular. The scale became more humane, and the small windows were a testament to an environmental approach and a focus on reducing energy consumption.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the architecture in Greenland can be described as a “fast architecture”, designed mainly to accommodate contractors and their economy. This was an unfortunate development, but again, things are changing for the better, bringing more focus to the quality of the architecture. For instance, the municipality of Sermersooq has approved an architectural policy – the first ever in Greenland.

Future Perspectives and Contemporary Design Examples

Challenges

Building process

There is no forest production in Greenland, so all building materials are shipped from abroad, mainly from Denmark. The only building material produced in Greenland is cement and concrete, which is not very sustainable. On top of this challenge, the climate is challenging, and the optimal time window for construction is short. Snow and sub-zero temperatures are a challenge on the construction site. Therefore, planning and precision are crucial aspects of the building process in Greenland, as any obstacles tend to increase costs.

With these obstacles in mind, and a tourism industry focusing on adventure tourism rather than mass tourism, minimalistic and temporary structures might be the way to go for Greenland when it comes to design in nature.

Architecture policy in Sermersooq

The municipality of Sermersooq has approved an architectural policy, the first of its kind in Greenland. The strategy is an important step to address the future of architecture and design in modern Greenland.

The policy describes four overall objectives, each addressing a different aspect of architecture in Sermersooq.

1. Identity-building architecture

The identity of the individual, the place, and the community.

2. Housing and quality of life

A house and a home must give something back and inspire.

3. Urban space and life in the city/hamlet

When designing the spaces between buildings, creating meeting places for the people, one must focus on materials and comfort.

4. Time and place

All design should involve using appropriate technology and beware of the context and surroundings. As an example, using high-end materials in a small hamlet might seem out of place.

Through their initiative Sermersooq Municipality is taking the lead in Greenland by defining the community’s architecture and design policy. This is an essential and welcomed contribution to the debate about how Greenland should design for tourism. Through their initiative Sermersooq Municipality is taking the lead in Greenland by defining the community’s architecture and design policy. This is an essential and welcomed contribution to the debate about how Greenland should design for tourism.

Trends, Tourism as a game changer

The population in most Greenlandic villages is decreasing – globalisation and urbanisation are also an issue in the remote Arctic areas. It will be interesting to see if tourism can create a new foundation for some of the small local communities in Greenland. Efforts are already underway to develop the tourism offering across the country.

In Ilulissat, the Ilimanaq Lodge opened in 2017. It consists of fifteen huts and a restaurant in a restored historical building – all in the village of Ilimanaq. Visitors get a unique nature experience and experience the culture and everyday life in an active Greenlandic village.

The Nuuk Icefiord Lodge is another example of a newly developed tourism concept located near the village of Kapisillit, 75 km from Nuuk.

Situated 3 km from the village of Kapisillit, the Lodge consists of 50 lodges and a restaurant overlooking the sea. A dirt road connecting the lodge with the village is part of the project.

Kapisillit only has 53 inhabitants, so the Lodge will accommodate more people than the entire population of the village. With full occupancy of the cabins, the village expects a significant increase in traffic and visitor numbers. According to the project owner, the cabins will create more life in the village, which is well in line with the municipality’s vision of developing Kapisillit as an attractive tourism destination and a green and sustainable settlement.

The architecture is modern and differs from the area’s architectural history. As Kapisillit is known for its small wooden houses with classic saddle roofs.

Visitor Centres

To strengthen tourism in Greenland, the Government is working on establishing several visitor centres throughout the country. The idea behind the project is to promote a strong, professional, and self-sustaining tourism sector to benefit a sustainable Greenlandic society. The visitor centres are expected to help spread the socio-economic benefits of tourism and ensure that the benefits from local tourism activities stay in the local communities.

Ilulissat Icefjord Centre

Ilulissat Icefjord Centre provides knowledge about the ice and its significance for life and people in Greenland. The ice is a rich source of information about variations in temperature, climate change, and the effect of the ice on nature and the cycle of nature. As the first official visitor centre in Greenland, The Ilulissat Icefjord Centre opened in July 2021.

The Norse gate in Qaqortoq

Nordboporten in Qaqortoq tells the story of the Vikings who settled in Greenland more than 1,000 years ago. Southern Greenland has hundreds of sites with ruins and remains from the time of the Norse settlers. The Arctic Farmers Visitor Center provides insights into life in Southern Greenland, from the Norse settlements and their disappearance until today, when warmer temperatures enable more crops to be grown and harvested in the area.

The Polar house of Tasiilaq

The Polar House in Tasiilaq tells the story of the East Greenlandic culture and the history of the great Arctic expeditions. The culture in East Greenland is formed by the harsh nature and inaccessible landscapes but also by the area’s rich wildlife and the proud Inuit hunting culture.

The Nature and Geocenter of Nuuk

Nuuk Nature and Geopark tells the story of the earth’s formation and the first life on earth. The first colonial settlement in Greenland was in Nuuk, and the 10,000 km2 Nuuk Fjord system is home to spectacular wildlife both on land, sea, and in the air. The earliest signs of life on earth, 3,800 million year old microbes, are found in the Nuuk Fjord.

The Inuit Centre, The land of the people

The Inuit Hunting Ground Centre in Sisimiut tells the story of the earliest migrations to Greenland, the traditional Inuit lifeforms, and hunting culture in the more ice-free tundra of Western Central Greenland. The area was declared a UNESCO World Heritage in 2018.

The visitor centres are linked to the three existing UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Greenland and sites that could potentially be added to the World Heritage List in the coming years.

Architecture and local knowledge

Greenlandic architecture is inspired by Danish and Nordic architecture. Some of the most important buildings in Greenland, like Katuaq – The Culture House in Nuuk and the Ilulissat Icefjord Centre are designed by Danish architects. The buildings are functional and beautiful, but some find it unfortunate that they are not designed by local architects.

The new visitor centres will represent Greenland and its architecture for many years to come, so one could argue that the design should be in the hands of local architects and designers. These ambitious projects represent an opportunity to challenge what Greenland architecture is and should be in the future – from a local perspective. The future calls for further studies and application of local knowledge in terms of design in nature. Hence, a global reach out of Greenland should engage and empower the local design community and local inhabitants in addressing their competencies and sensibilities in dialogue with global expertise and know-how.