By Miina Jutila & Tuuli Kassi

Finns are proud of their country’s nature – its forests and lakes, the archipelago in the south and the rounded fells in the north. However, nature is subject to many conflicting interests, from nature protection to forestry, mining, and tourism.

Good design can alleviate these conflicts. Sustainable use of resources is essential, and through quality design, possibilities to experience magnificent natural environments can be offered while at the same time protecting nature from the wear caused by visitors. New interpretations of the age-old boardwalks are an excellent example of this and in addition, they enable accessible nature tourism. Light structures, such as wind shelters, serve well for gaining experience of different recycled materials, and remote wilderness huts could benefit from circular water use practises and off-grid electricity, for example.

Connection to nature supports our wellbeing, and going off-grid can be very restoring at times. These positive effects can be achieved in the numerous Finnish national parks and nature preservation areas from the capital region in the south to the untouched wilderness of the north.

Finnish nature and tourism

Midnight sun, autumn foliage and aurora borealis

The imprint of Finland on a map resembles a tall maiden – the skirt and arm of which were cut off by war. The land area of 338,500 km2 reaches from the Baltic Sea in the south almost to the Arctic Ocean in the north, separated only by a narrow strip of Norway. In the west, the Gulf of Bothnia and the rivers Tornio and Muonio run between Finland and Sweden, whereas in the east, the country shares a long land border with Russia – Finland is just a stone’s throw from Siberia.

Interactive Map

The climatic differences between the south and north are significant – one-third of Finland’s total span of 1,160 km is above the arctic circle. From the south coast, scattered with rocky islands, to the ancient, rounded mountain tops in the north, Finland is home to several different nature types, the most delicate of which are indeed the archipelago and the Arctic areas.

Excluding these extremes, Finland is characterised by forests and lakes: more than 10% of Finland’s territory is covered by water – there are 57,000–168,000 lakes depending on the definition – and about 75% of the land area is covered with trees. Most parts of Finland belong to the taiga zone, with spruce and pine as dominant species. In spite of a rather narrow variety of tree species, many different biotopes and landscapes can be found. Different types of mires cover up to a third of the terrain. This abundance of water is optimal for migratory birds, which arrive in enormous amounts for the summer season.

Towards the north in Lapland, which spreads over northern Finland and its neighbouring countries, forests diminish into dwarf birches and shrubs, and the open landscape is spotted with fells, the highest of which rise above the treeline. However, due to climate change, the tree line is rising, which imposes changes to the landscape.

The northern parts of Lapland belong to the delicate arctic tundra zone. In the hollows between the fells, there exists a unique and curious bog type, palsa, with its peat mounds of permanently frozen cores. As the climate is becoming warmer, the palsa bog type is severely endangered.

All the different growing zones in Finland experience four distinct seasons. In the north, winters are dark, cold and snowy, while in the spring, sunlight sparkles on the snow that still remains. In addition to winter activities and snow, tourists are attracted by the arctic light shows in the sky, the aurora borealis. Summers are short but full of sunlight, day and night, and autumn trees are crowned with a natural colour display of different hues of yellow, orange and red, ruska in Finnish. During summer and autumn, hiking is the most popular tourist activity.[1]

In this climate of extremes, people need shelter from the elements in order to enjoy the seasons to the fullest.

Nature protection and tourism: national parks

Parallel to growing tourist interest in northern Finland, a lot of effort has been put into preserving the natural areas. Around 12% of all the natural lands in Finland, and up to 20% in the north, are different types of conservation areas: strict nature reserves, private and public conservation areas and national parks. National parks are open to all visitors, as long as they follow the park rules, whereas strict nature reserves require permission to visit, with a valid reason such as research purposes.

Forest owners who volunteer their lands for preservation can receive compensation from a national conservation programme, METSO, running from 2014 to 2025. The forest’s suitability for conservation and the compensation amount are defined by the quality of trees as well as the biotopes, which need to be diverse or rare.

One reason for the large number of nature reserves in the northern part of the country is the preservation of geological formations found there. These areas are regarded as national landscapes, outlined in every Finn’s memory as depicted by great Finnish artists in the time preceding independence at the beginning of the 20th century.

Koli in northern Karelia inspired many artists such as painters Eero Järnefelt, writer Juhani Aho, composer Jean Sibelius, and photographer Into Konrad Inha. Painting by Eero Järnefelt, Landscape from Koli, 1928.

Finnish National Gallery

Finnish National Gallery

The initiative to establish the national parks was launched back in 1880, and after many long discussions and much preparation, the first national parks and nature reserves were founded in 1938. They were administered by the Finnish Forest Research Institute, a subordinate agency to the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Some of the newly established parks were in the territories that were lost due to the war, and the ones that remained were all situated in Northern Finland. The second wave of national parks in 1956 brought more geographical variety, and today, there are 40 national parks all around Finland.

National parks are state-owned areas, the use of which is decreed by law. Originally, the parks were considered as nature conservation areas, not as tourist attractions, nevertheless, it wasn’t forbidden to visit them. Beginning in the 1970s, national parks were developed more systematically, including maintenance strategies and criteria for new national parks with complementing biotopes and natural values .

As the focus moved from nature preservation to combining nature with tourism, more supporting infrastructure was required to facilitate visits and to protect the natural habitats from visitors. Marked trails with bridges and boardwalks, networks of wilderness huts, dry toilets and designated campfire areas were built. Often there is a Nature Centre in the park, offering exhibitions and information.

Today, a state-owned enterprise Metsähallitus (Finnish Forest Administration), which operates under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, manages all the national parks and their infrastructure. Metsähallitus maintains a website with an abundance of information and guidance on national parks and their code of conduct, including staying on marked trails, lighting fires only in designated areas, and following the “leave no trace” guidelines.

Statistics of visitors per year in sites managed by Metsähallitus:

– 40 National Parks: almost 4 million visits in 2020, up 23% from 2019 (3,2 million)

– Natural and historical sites: about 8 million visits in 2020

https://www.metsa.fi/en/outdoors/visitor-monitoring-and-impacts/visitation-numbers-and-visitor-profiles/

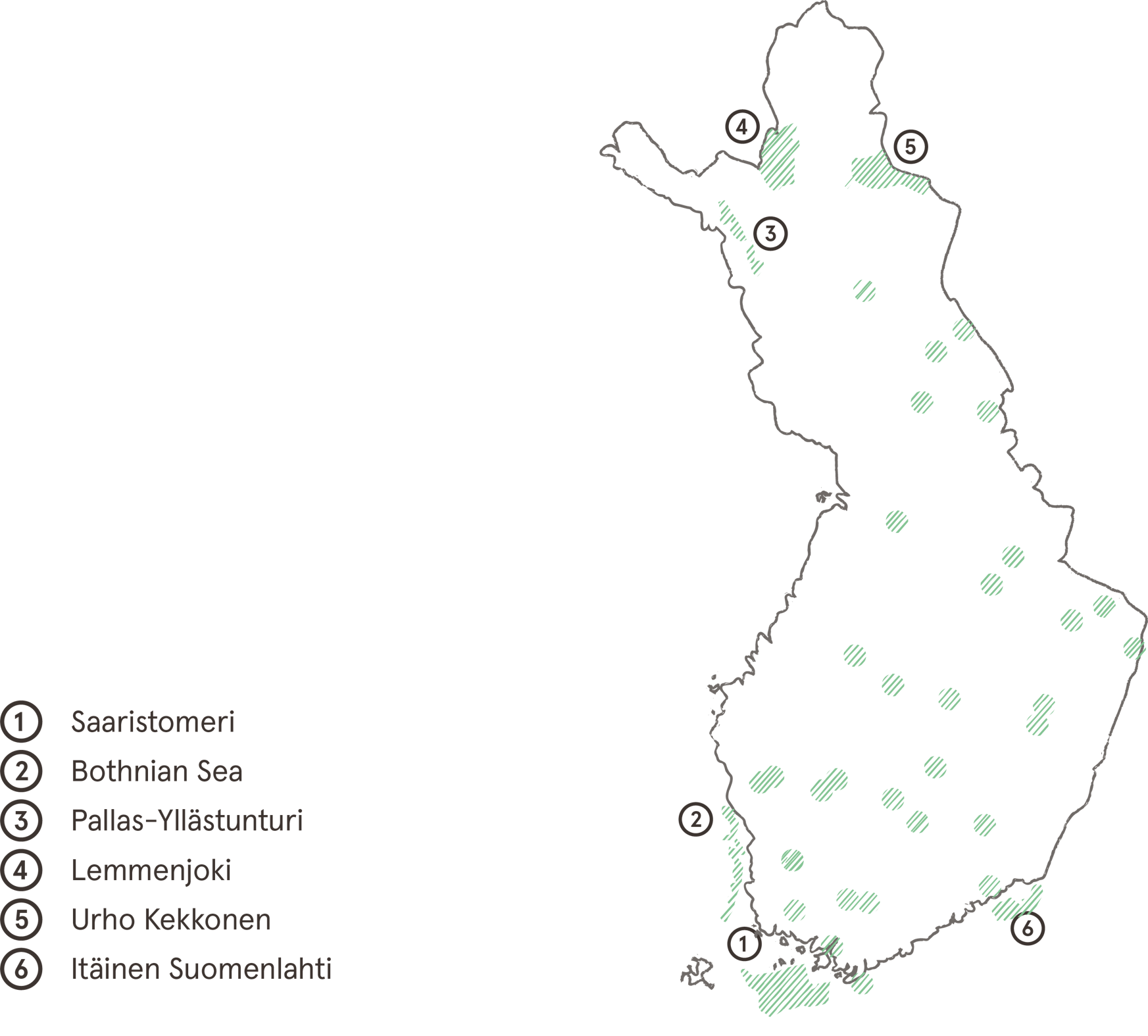

National Parks

Location of the six largest of the 40 national parks in Finland

In addition to national parks and nature preservation, Metsähallitus also manages all other state-owned forests and their logging. The forest industry has played a major part in the growth of Finland’s economy – and it has also left its marks on the landscapes. Some conflicting interests include, on one hand, the desire to get more timber and other wood products out and on the other needing to preserve sustainable tree growth and carbon sinks, biodiversity, the traditional livelihood of reindeer herding, as well as the recreational quality of the forests. Some recent studies have indicated solutions for the financial equation by monetising, in addition to timber, the multiple income streams of sustainably managed forests, such as carbon sequestering and recreational values.

Everyman’s rights (fin: Jokamiehen oikeus)

Public access rights are known as everyman’s rights in Finland and give unrestricted access to and the right of use of most natural areas to everyone. The concept is one of the country’s most influential policies directing people’s activities in nature. It has its roots in the ancient tradition of open use of land of all the nomadic people who first inhabited Finland. It suggests enjoying the natural environment and the berries and fruit therein as public commons, allowing everyone to benefit from them regardless of land ownership. Everyman’s right is not a law in itself but a principle that prevents setting new laws that would restrict this right of use.

Basically, everyman’s rights means that everyone living or staying in Finland is allowed to use the natural areas, also on privately owned land, as long as they cause no disturbance nor permanent harm to the environment and the livelihoods of landowners. The right includes tenting and moving by walking, cycling, skiing or, in some cases, horseback riding. However, the principle does not apply to domestic property, cultivated fields in the summer and other land areas under specific use.

With rights come responsibilities, and different restrictions apply to protecting the natural ecosystems and landowners’ livelihoods. For example, it is prohibited to cut or damage standing trees, whether dead or alive, to light an open fire, and to litter. Off-road driving with vehicles is only allowed with the landowner’s permission. Birds and other animals are not to be disturbed during the breeding season. Permission from the authorities is needed for hunting and fishing, and hunting also requires permission from the landowner.

Thanks to everyman’s rights, hiking in nature and collecting berries and mushrooms are popular hobbies throughout Finland.

Strategies and planning related to tourism and nature

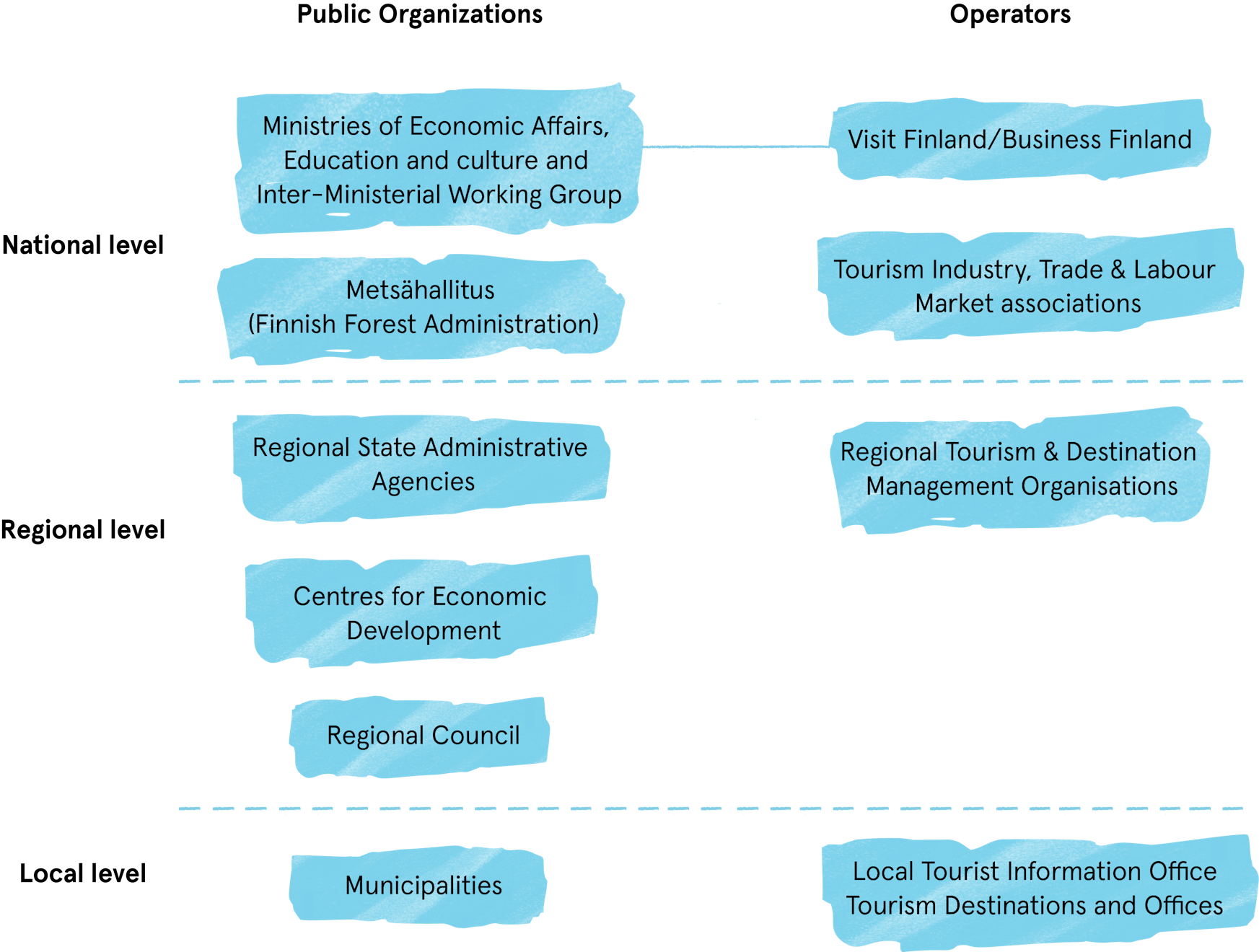

In the Finnish government, nature tourism falls under the governance of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, and the Ministry of the Environment.

Finland’s national Arctic Strategy was first published in 2013 and updated in 2016. The strategy listed three focus areas: arctic know-how, sustainable tourism, and infrastructure solutions.[2] The new Arctic policy strategy, approved in June 2021, identifies four priority areas for Finland’s Arctic activities: climate change, inhabitants, expertise, and infrastructure and logistics. The strategy states that all activities in the Arctic region must be based on ecological carrying capacity, climate protection, principles of sustainable development, and respect for the rights of indigenous peoples. Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy extends to the year 2030.[3]

Sustainable tourism is also recognised in Finland’s national tourism strategy for 2019–2028. Its promotion continues in a project run by Visit Finland, which offers information, support and a Sustainable Travel Finland Label for companies that adopt sustainable practises. Furthermore, in 2018–2019, the Arctic Sustainable Destination Finland project run by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment promoted sustainability for travel companies and destinations in the north. Also, the Lapland tourism strategy for 2020–2023 positions sustainability at its core.[4]

The Land of National Parks project running from 2019 to 2021 combines the national parks of Oulanka, Hossa, Riisitunturi and Syöte, all just south of the Polar Circle, in joint marketing and producing training materials on sustainability for businesses. The project, funded jointly by the EU, the State of Finland, local municipalities and enterprises, promotes lighter ways of enjoying nature through activities such as biking, paddling, and wildlife photography. The project funds several improvements on nature infrastructure in national parks and other nature attractions.[5]

Nature tourism and recreational use of nature were also recognised in the Ministry of the Environment’s strategy and action plan for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, running from 2012 to 2020.[6] According to the plan, the aforementioned should be developed within the framework of nature values and preservation of prerequisites for the traditional livelihoods of the Sámi, the indigenous people of Lapland. Environmentally responsible tourism is seen as a prerequisite for preserving the value and attraction of the natural areas. The action plan states that the use of natural sights should be developed from the perspective of accessibility and demand while maintaining sustainability and preserving biodiversity in the areas and in land use planning.

Organisational chart of tourism bodies

In cities, too, a delicate balance is to be found between densifying and preserving urban nature and access to recreational areas. In Helsinki, the city launched a Maritime Strategy in 2018, intending to offer residents new recreational opportunities in maritime areas – Helsinki has a 130 km long shoreline. As the population in cities grows, easy access to nature becomes more and more valued – and even more so in times like the pandemic.

Since 2005, in conjunction with the GoExpo Fair, The Finnish Fair Foundation has organised an annual vote for the best hiking areas in Finland. The prize has gone to larger areas, such as Hossa National Park near Kuusamo and Rokua Geopark near Oulu, as well as smaller destinations, such as the “Birgitan polku” trails in the municipality of Lempäälä near Tampere. What is notable here is that regardless of the size of the area, in most of the awarded sites, the infrastructure is well designed, supporting a pleasant visit. In addition to recognition and visibility, the winning attraction gets a small stipend to further develop its services.

Design traditions and local craftsmanship

From wilderness huts to hotels - history of tourism and nature in northern Finland

Originally, travellers were attracted to northern Finland by the landscapes and romanticised notions of wilderness and Sámi culture. Lapland was only accessible to a few people and accommodation was mostly arranged in local homes. In the 19th century, some viewpoints and shelters were built for admiring the scenery and the midnight sun.[7]

At the beginning of the 20th century, an organisation called Suomen Matkailija-yhdistys (Travellers Association of Finland) was one of the first to promote tourism in Lapland as a way to help the newly independent nation gain recognition from the rest of the world. The first accommodation buildings for leisure travellers were built near the recently founded national parks, close to the scenic views and hiking grounds. Several notable architects of the time were involved with state-funded hostel projects, which were primarily small-scale buildings gently fitted into the landscape. Usually, they were situated near waterways and roads, but an exception was the Pallas Hotel (1938), which was permitted within the national park of Pallastunturi fell and later had considerable impact on the delicate natural environment due to expansion.

Pallas Hotel in the Pallastunturi National Park. Architects: Väinö Vähäkallio and Aulis Hämäläinen, 1938.

Aarne Pietinen Oy / Finnish Heritage Agency

Aarne Pietinen Oy / Finnish Heritage Agency

Travellers’ accommodation “Inarin Matkailumaja” in Inari. Architect: Väinö Vähäkallio, 1939.

Otso Pietinen / Finnish Heritage Agency

Otso Pietinen / Finnish Heritage Agency

After the second world war, a big part of Lapland’s infrastructure was in a state of devastation. Little by little, the north started seeing a rise in visitor numbers and several new accommodations were built. Sports and physical health were highly valued, and hiking and cross-country skiing were typical ways for tourists to enjoy nature.

Later, downhill skiing became fashionable, and many of the old mountains were subjected to ski resorts and strong landscaping efforts to produce suitable hills for the sport. In the process, several delicate landscapes were ruined for summer uses, and healing these areas might well take a few hundred years. Still today, northern tourist resorts are under pressure to create more accommodation and build higher than the surrounding environment and landscape can take. Local planning administrations must balance between pressures to ensure investments, secure livelihoods and preserve environmental qualities.

Open wilderness huts (fin: Autiotupa)

Wilderness huts have been built at least since the early 18th century, initially for postmen, officials and other travellers who had to cover long distances and stay overnight along the way. The huts were small, simple chambers with turf roofs, situated at a distance of one day’s travel from each other. Later, the state provided log houses for this purpose along the main routes. After the second world war, the newly established national parks in Lapland were equipped with open wilderness huts for hikers.

In the 1960s, a more tight-knit network of open-use wilderness huts was developed. The management of the huts was transferred to the Finnish forest administration Metsähallitus, and new huts were often adapted from other uses, such as lumberjacks’ and gold diggers’ huts and horse stables.

The Perum-Ämmir postal hut was built near Utsjoki in the 1890s. Later it was used as an open wilderness hut. Towards the end of the 20th century, the hut was relocated to a museum area in Karigasniemi.

Martti Linkola 1978 / Finnish Heritage Agency

Martti Linkola 1978 / Finnish Heritage Agency

Metsähallitus holds archives of standard drawings, which can be used for traditional style wilderness huts. Currently, the drawings are being updated. Metsähallitus also commissions architects to design huts with contemporary architecture. As the huts are situated in national parks, timber and other building materials must be transported to the site. Prefabricated elements work well for remote locations where workers are scarce. The elements are mainly transported on snowmobiles in winter to preserve the forest floor.

Metsähallitus has commissioned the design open and rental wilderness huts in Rautulampi [1]in the Urho Kekkonen National Park. The huts were completed in summer 2021. Architect: Manu Humppi

Manu Humppi

Manu Humppi

Open wilderness huts are the most common type of free-use huts found in Finland. They are meant for one-night stays during a hike and are located in roadless backwoods. Other types include open day huts, open turf huts and Lapp pole tents. These are suitable for a short stop and rest during the day.

All the open-use huts are restricted to individuals and small groups on non-commercial tours. However, there are also rental wilderness huts that may be used by bigger groups and tour providers as well. The same codes of conduct apply to all wilderness huts: the hut is to be left in the same condition in which it was found, including chopping firewood for the next visitors.

The Kultala wilderness hut along the Ivalojoki river was built in the 1990s following a traditional design.

Tuija Kangasniemi

Tuija Kangasniemi

Wind shelters (fin: laavu, kota)

Along many nature trails, there are wind shelters for cooking food and resting in the daytime. The traditional types of wind shelter found in northern Finland are based on the Sámi kota, a traditional pole tent. The simplest form is a structure of wooden poles covered with fabric, while other versions have walls, a roof, and perhaps even floorboards. What they all have in common is that they are not closed in by walls on all sides. Often, the shelters offer a place for a campfire, either in the centre of the shelter or outside in front of the structure.

As with the wilderness huts, the shelters are publicly managed, by Metsähallitus or the municipality, depending on the land ownership.

Kuninkaanlaavu along the Ounasjoki river near Rovaniemi is a traditional style shelter with a hexagon log base and a pointed roof.

Terhi Tuovinen / Visit Lapland

Terhi Tuovinen / Visit Lapland

Revontulilaavu near Ylläs and Äkäslompolo is a shelter to appreciate the aurora borealis. Architect: Raul Reunanen

Raul Reunanen

Raul Reunanen

A light shelter structure on Vasikkasaari island in Helsinki. Architect: Nomaji Landscape Architects

Nomaji Landscape Architects

Nomaji Landscape Architects

A modern shelter for enjoying nature on Kaunisharju near Sallatunturi. Architect: Biotope Architects

Anna Pakkanen

Anna Pakkanen

Duckboards and boardwalks (fin: pitkospuut)

Finnish forests are often patched with swamps or mires, especially in the nature reserves where the swamps haven’t been dried out for turf collection. Whenever a hiking route passes through a swamp, boardwalks are needed to guide hikers safely through the area, keep their feet dry, and protect the surrounding ground from trampling. In national parks, the boardwalks are managed by Metsähallitus, while some are maintained by the municipalities.

Traditional wooden duckboards are composed of two or three parallel boards posed on short log supports. Modern boardwalks can be wider to accommodate wheelchairs and other aids. Made of untreated wood, the boardwalks typically need to be replaced every 10–15 years. As they are often located deep in roadless backwoods where transporting material and workers can be demanding, tests are being carried out with alternative materials such as steel, recycled plastic, and plastic composites.

The sustainability of material choices is a balancing act between economic and circular aspects. It appears that the traditional untreated wood remains the most sustainable material, from the point of view that it biodegrades safely back into nature after serving its time. Siberian larch, which is highly durable, is used in some places. Unlike wood, steel and plastic structures need to be transported back from the forest when they are at the end of their cycle, and in addition, they tend to be more slippery when wet. Moreover, mesh structures can be harmful to animals, for example, to dogs’ feet. According to visitors’ opinions, wooden structures are most preferable.

Traditional duckboards over a mire in Pyhä–Luosto National Park.

Heta Leinonen

Heta Leinonen

Accessible boardwalk in Isokuru in Pyhä–Luosto National Park.

Heta Leinonen

Heta Leinonen

Boardwalks in Pyhä–Luosto National Park.

Heta Leinonen

Heta Leinonen

Traditional livelihood and housing

Reindeer herding is one of the traditional livelihoods of the Sámi people in northern Finland. In earlier times, reindeer herders led a nomadic lifestyle, moving long distances with their herd: from the forested areas in the winter all the way up to the Arctic Ocean for the summer. The Sámi cultural rules kept reindeer numbers to sustainable levels, and their overall approach was to leave no trace in the landscape. Permanent structures did not play an important part in their culture, whereas natural sites were assigned with cultural meanings.

For the nomadic tribes, the traditional tents consisted of two supporting arches with secondary branches and were covered with fabric or reindeer skins. More permanent accommodation included huts made from a base of interlocking logs in the form of a square, hexagon, or octagon, with an upwards narrowing roof structure made of branches and roofed over with turf or other natural materials. Some houses were half-dug into the ground. From the 18th century onwards, different traditional hut types were mainly replaced by square log houses.[8]

Nowadays, the Sámi live in permanent homes, and the herds, managed with the help of motorised vehicles, move within smaller areas. Traditional design structures, such as fences for reindeer separation, could help leave a mark of the local indigenous people’s cultural heritage and support the culture’s survival in the long term.

Turf chamber.

Erkki Vihonen, 1960–1979 / Finnish Heritage Agency (CC BY 4.0)

Erkki Vihonen, 1960–1979 / Finnish Heritage Agency (CC BY 4.0)

A traditional log house in Siida outdoor museum.

Siida Museum

Siida Museum

Current designs and future visions

Nature tourism is trendy!

For the past twenty years, nature tourism has been a growing trend, and the Covid-19 pandemic has brought it to a peak. Despite the international travel restrictions, 2020 saw a 23% growth in visits to national parks.

Based on the long-term growth in the number of visits, it is estimated that they will remain high even after the pandemic. In 2021, the supplementary budgets and future investment funds provided by the Parliament of Finland have increased the financing of national park infrastructure repairs threefold. This makes it possible to welcome the growing numbers of people to enjoy nature now and also in the future.

The benefits of nature tourism on our wellbeing

Research is gathering increasing evidence about the positive effects of spending time in nature. A walk in the forest soothes the nervous system, lowers blood pressure and enhances immune system functions. We are not separate from nature. This could be one take-away for modern tourists in Lapland from the Sámi culture – a sense of being one with nature. The flip side is that when the Earth suffers, so do humans.

A growing trend in nature tourism is to enjoy the peace and quiet. Nature and hiking induce slowing down from city-dwellers’ hectic everyday rhythms. According to studies, designed structures can help travellers stop and experience specific sites and natural forces or direct them to notice the details and engage their senses.[9] A sense of cohesion can be enhanced, for example, with on-site information on the geological time frames of the surrounding landscape, offering points of view to pre- and post-humanistic eras.[10]

An interesting place for experiencing the coexistence of nature and human culture is the stone gorge of Aittakuru near Pyhä Fell, a magnificent natural formation serving as an outdoor concert hall. Only narrow boardwalks and stairs lead down to the stage while spectators are seated some 50 metres higher up on the slope of the gorge. The natural formation created by the ice age and covered with fragmented rock creates an acoustically singular environment where a mere whisper can be heard over the 400-seat grandstand. In 2020, the stage was damaged in an avalanche but was repaired in time for the Pyhä Unplugged 2021 festival.

Aittakuru stage viewed from the stand at Pyhä Fell. The photo was taken in 2020 after an avalanche damaged the structures, which have now been repaired.

Heta Leinonen

Heta Leinonen

Threats to overcome

Although forests cover 75% of Finland’s land area, many ignore that only about 3% of the territory is primary forests where there are no clearly visible indications of human activities and where the ecosystems are still undisturbed. Up to fifteen nature types in northern Finland are considered endangered. For example, the arctic palsa bog biotope with its peat mounds is gravely affected by climate warming as it depends on permafrost. The warming climate shortens the snow cover period and raises the forest line on the northern mountains, affecting the ecosystems and altering the balance of species. Climate destabilisation also means changes in rain amounts and wind conditions and brings new diseases and pests, all of which can affect the northern natural environment in unexpected ways.

The main risks to the northern wilderness in Finland include town, traffic and tourism plans, as well as intensive forestry methods, machine-based gold-digging and other mining activities. Also overgrazing and the use of motorised vehicles in roadless areas leave their traces in the sensitive biotopes. Vehicle traffic noise is also a pollutant that disturbs sensitive species in the summer breeding season. Popular hiking trails erode the ground and affect animal and plant life. Increasing visitor numbers require sturdier structures to guide hikers and safeguard the surrounding nature.

Large hotel resort developments pose a threat to biodiversity and delicate landscapes: hotels are keen to offer their guests fell-top views, but once the fell’s natural state is lost, it is difficult to restore. In the Saariselkä ski resort area, an urban planning competition was arranged in 2008 to counteract the pressures of major commercial developments. A master plan was developed based on JKMM Architects’ winning design, which proposed carefully placed densifying with mostly small-scale buildings. Surprisingly, this created more accommodation capacity than big scale hotels and resorts would have offered.[11]

Densifying existing town and resort centres is often more respectful of the environment than big developments. On the other hand, densification can also weaken the wilderness elements in the centres and thus affect the experience of visitors who wish to have their accommodations close to nature.[12]

However, many travellers are becoming more conscious of the sustainability issues of tourism. According to a study, up to a third of consumers would prefer an environment-friendly option when available.[13]

Circular and regenerative design

The circular economy is an excellent framework for sustainable tourism with its principles of regenerating natural ecosystems and designing out pollution and waste, for example, by using recycled materials. Good nature design solutions include using renewable energy sources and local biodegradable materials and recycling biological nutrients, for instance with the use of dry toilets.

Many circular approaches are already in use in the design of nature infrastructure. A good example of this are the Kintulammi nature reserve shelters, which reuse entire or parts of existing structures. Also, minimising and preventing waste is essential. In several places, visitors are encouraged to do trash-free hiking by not placing any bins along the trails. One example of a designer solution for circular off-grid housing is the concept of Majamaja. This small hut has energy and water autonomy by using rainwater and solar energy. The hut can be placed on the site without any groundworks, and it can also be removed without a trace. Could these kinds of structures offer a solution for future wilderness huts?

Saarijärvi shelter in Kintulammi nature reserve near Tampere is made from reused parts of a smoke sauna. Architect: Malin Moisio

Malin Moisio

Malin Moisio

Majamaja, a concept for an independent ecological housing unit. Architect: Pekka Littow

Marc Goodwin

Marc Goodwin

Mining is a major branch of industry in northern Finland. An inevitable part of a mine’s lifecycle is the eventual end of cost-effective operations. In this context, regenerative design becomes an important aspect when environments disrupted by human activities such as mining are restored to their natural states or transformed to recreational uses.

An example of such a remediating project is the Zeniitti area plan in Kempele, south of Oulu, where a former stone mining hole now filled with water is to be landscaped into use as a lake for swimming and other recreational activities. The lake will form the heart of a new housing and tourist attraction area, which is easily accessible by train and aeroplane and has excellent connections to the surrounding hiking trails.

Zeniitti area plan visualisation by MUUAN Architects

MUUAN

MUUAN

Another example is a plan for a holistic artwork called Luonnontuhopuisto (‘The park of natural destruction’) by artist duo IC-98, landscape architect Mari Ariluoma and architect Maiju Suomi. The park will use phytore- and mycore-mediation to clean the site's soil in an old mine while offering a place for contemplation of human impact on nature. In 2021, the artists are looking for a suitable site for the piece.

Doing less as a sustainability strategy

In the Sámi philosophy, everything has a spirit. For this reason, leaving the natural sites that have been identified as Sámi sacred places, seita, untouched is an especially important part of respecting the local culture. This has not always been the case, but a change in the tourism practises can already be detected. An example of this is the seita on Ukonkivi island in the Lake Inarinjärvi in the north-eastern part of Lapland.

In the 1980s, a pier was constructed for visitors to dock on the island, and Metsähallitus installed stairs for climbing up to the summit. In 2019, some 11,000 tourists visited the site, until that autumn, the local ferry company and cruise organiser decided to stop landing on the island out of respect for the sacred place. Following this, in 2020, Metsähallitus and the Finnish Transport Infrastructure Agency decided to tear down the structures giving easy access to the island. The Ukonkivi island was suggested for a UNESCO World Heritage listing in 2008. The Protection of Antiquities Act protects the island to some extent, albeit it doesn’t forbid visiting.

Ukonkivi island in the Lake Inarinjärvi is a sacred place of the Sámi people.

Ninara / Flickr

Ninara / Flickr

Ninara / Flickr

Ninara / Flickr

All in all, there is a positive development with strategies guiding towards better directions, local travel organisers starting to see the benefits of sustainable practises, and designers creating new aesthetics and functions with circular thinking. All these and much more are needed, as nature tourism is becoming more and more popular. We need to protect nature from too much human influence while still allowing people to enjoy experiencing natural areas. Good design can guide behaviours and use materials in ways that respect the environment.

Notes

1 More information on Finnish nature may be found here: https://finland.fi/life-society/nature-in-finland/

2 Documents related to the Arctic Strategy by Prime Minister’s office can be found here: https://www.arcticfinland.fi/EN/Documents

3 Finland’s Strategy for Arctic Policy (2021) by Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s Government (pdf): https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/163247/VN_2021_55.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

4 Information on the older version of the Lapland tourism strategy in English: http://www.lappi.fi/lapinliitto/en/development/travel

5 More information on the results of the Land of National Parks project: https://www.nationalparks.fi/landofnp

6 The national strategy and action plan for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, entitled “Saving Nature for People” https://ym.fi/en/national-biodiversity-policy

7 Dr.Tech.(Arch), architect Harri Hautajärvi has studied the history of architecture of Lapland’s tourism. His dissertation (in Finnish) Autiotuvista lomakaupunkeihin – Lapin matkailun arkkitehtuurihistoria (Aalto University, 2014) is the main source for this chapter.

8 More information on Sámi culture and design structures can be found in publications (text in Finnish but plenty of pictures included) Pekka Huima: Ihmisen jälki (2015) and

Manu Humppi: Kammit ja autiotuvat, Lapin kairojen kulttuuriperintö (2014)

9 Rantala and Mäkinen, 2017

10 Rantala, et al, 2020

11 Hautajärvi, 2014 p. 290

12 Uusitalo, 2017

13 Holiday Habits report by British ABTA, 2015

Author information

Miina Jutila, Architect M.Sc., Head of Communications, Archinfo Finland, miina.jutila@archinfo.fi

Tuuli Kassi, Architect M.Sc., Expert commissioned by Archinfo Finland